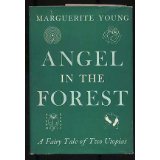

MARIANNE HAUSER’S 1946 REVIEW OF MARGUERITE YOUNG’S

ANGEL IN THE FOREST

First published in the Sewanee Review, vol. 54, no. 2, Spring 1946. Copyright 1946, 1974 by the University of the South. Reprinted with the permission of the editor.

THE DUAL INTENTION

THE DUAL INTENTION

BY MARIANNE HAUSER

In Angel in the Forest, Marguerite Young has found a strikingly regional subject matter, one transcending regionalism, to express both her wit and fantasy to the fullest, to illuminate the American scene with vision. Her region is nearly that of, though it purports to be concerned preeminently with the Indiana corn field and the cultural factors diversely at play there, the lost Atlantis, the city of Campanella, other marvelous matters. The dual intention, reality and unreality, is made clear from the first page-when you cross the Wabash to that land by a “creaking ferry,” the other passengers being only two blind mules. Here, myth extends its many branches like an octopus, along with the filling station, along with hollyhocks and “spinsters numerous as hollyhocks.” The subtitle, A Fairy Tale of Two Utopias, is thus a meaningful indication of surrealistic and realistic events in a pat tern of infinite motion. New Harmony, Indiana village, laboratory, and nameless graveyard of man’s aspiration for the ideal happiness, both social and individual, both of heaven and earth, becomes, under Miss Young’s eyes, the one gloomy, the other prismatic, a spectacle of the world at large, contradictory as the human soul, even more contradictory, since it takes in harsh aspects other than the soul-for instance, the climate, its extremes of hot and cold. A view of life as homely as that of James Whitcomb Riley, Hoosier poet, is combined with a view of life as unhomely as that of Swedenborg or Bishop Berkeley of Cloyne, John Locke’s mind, born into the world as a blank page-here frequently discussed-takes on the wild, eccentric coloration of E. T. A. Hoffmann, German fairy tale writer. There are all kinds of conspiracies going on within a text which escapes its boundaries.

“What dream among dreams,” Marguerite Young asks, “is reality ?” Such a question sets the key for the entire procedure.

At the beginning of the last century, two divers dreams, ancient in origin, converged on the banks of the Wabash far away, Father Rapp’s golden New Jerusalem, a city foursquare as measured by the burnished reed-both Biblical reed and Jimson weed which grow today in a still unlegislated country; and Robert Owen’s equally unrealizable rectangular community of reason. Father Rapp, founder of the first Utopia, a Scriptural communism, promised bliss eternal in heaven, “when this green earth should be destroyed by violence, by poisonous hailstones.” Robert Owen, his successor, founder of the second Utopia in a village deserted by the Rappites, made the more difficult promise of bliss eternal on earth, which paradoxically enough was very gray in his era, though he held it to be indestructible. For Father Rapp, the earth was in its springtime–for Robert Owen, the earth was in its autumn. The Owenites had not even enough energy to harvest the hops in that field where, so short a time back, the angel Gabriel had promised that men should be a “confluence of bright sunbeams.” The Owenites were easily discouraged, having no angel. Father Rapp, long-bearded patriarch from cloudy Wurtemberg, a businessman par excellence, both “mystic and murderer,” planned for his not-too-distant heaven by means of hard labor, the whiskey trade, strictly enforced celibacy on all but pigs, sheep, goats, the animal kingdom (on which celibacy Lord Byron watching from afar, wrote a caustic canto, “Don Juan”). Robert Owen, father of the British labor movement and many societies for the real advancement of the human race, visualized an Eden of Children, such as he had established at New Lanark cotton mills, shorter and shorter working hours, mental independence, a triumph over all mythologies. The Devil (perhaps in league with the shades of Father Rapp and company ) was preparing “a hole deep in the polar ice to swallow Robert Owen’s soul,” according to one of the many popular rhymes on the subject of Elysium.

At the beginning of the last century, two divers dreams, ancient in origin, converged on the banks of the Wabash far away, Father Rapp’s golden New Jerusalem, a city foursquare as measured by the burnished reed-both Biblical reed and Jimson weed which grow today in a still unlegislated country; and Robert Owen’s equally unrealizable rectangular community of reason. Father Rapp, founder of the first Utopia, a Scriptural communism, promised bliss eternal in heaven, “when this green earth should be destroyed by violence, by poisonous hailstones.” Robert Owen, his successor, founder of the second Utopia in a village deserted by the Rappites, made the more difficult promise of bliss eternal on earth, which paradoxically enough was very gray in his era, though he held it to be indestructible. For Father Rapp, the earth was in its springtime–for Robert Owen, the earth was in its autumn. The Owenites had not even enough energy to harvest the hops in that field where, so short a time back, the angel Gabriel had promised that men should be a “confluence of bright sunbeams.” The Owenites were easily discouraged, having no angel. Father Rapp, long-bearded patriarch from cloudy Wurtemberg, a businessman par excellence, both “mystic and murderer,” planned for his not-too-distant heaven by means of hard labor, the whiskey trade, strictly enforced celibacy on all but pigs, sheep, goats, the animal kingdom (on which celibacy Lord Byron watching from afar, wrote a caustic canto, “Don Juan”). Robert Owen, father of the British labor movement and many societies for the real advancement of the human race, visualized an Eden of Children, such as he had established at New Lanark cotton mills, shorter and shorter working hours, mental independence, a triumph over all mythologies. The Devil (perhaps in league with the shades of Father Rapp and company ) was preparing “a hole deep in the polar ice to swallow Robert Owen’s soul,” according to one of the many popular rhymes on the subject of Elysium.

Both Utopias failed dismally–Rapp’s being a financial success but a spiritual loss, Robert Owen’s being a financial loss though, in the last analysis, perhaps not a spiritual loss. The paradox suggests a poem of Browning’s. At any rate, the exodus of the Rappites was followed by the disintegration of the Owenite settlement before it was hardly established in what was perhaps “a fatal atmosphere.” For instance, the germs of malaria had already been released. Our heroes are not, in fact, Rapp and Owen-but populations, inclusive of the Rappite hens and roosters who dwelt outside Utopia, inclusive of the community of drunks which built its citadel at the gates of Owenite Utopia, inclusive even of “the little goat who, in 1940, cried and cried with its fleece caught on a thorn bough.” All that remained of New Harmony, in 1940, was human nature and the spectre of two enchanting dreams which, Jehovah’s and Rousseau’s, could not pass away. An angel’s footprints in stone, the maze where the Rappites had wandered, the black locust trees which the Rappites had left standing as their most macabre monument. Of the Owenites, fewer relics, fewer monuments, since their contribution to society had to do with legislation and government in all nations. Of the Owenites, only the golden rain trees which were to cast their shadows over “a new moral world,” when there should be neither crime nor punishment- not one sentient creature crying. “Utopias of the past seemed, in spite of their shade trees, not so tangible, finally, as Miss Hobbie and Miss Duckie, old sisters carrying their feather pillows to the show where the seats were hard to set on-sneaking in to see Clark Gable. All mankind seemed not so real as one lonely, frostbitten character, like the man who died with his feet in the ashes of the cold stove last winter, or was it winter before last ?” People were still betting on imaginary horses-like those at the race track at Dade Park, like those of the Apocalypse, too. Roosevelt was a white man riding on a white horse. Hitler was a brown man riding on a brown horse.

Both Utopias failed dismally–Rapp’s being a financial success but a spiritual loss, Robert Owen’s being a financial loss though, in the last analysis, perhaps not a spiritual loss. The paradox suggests a poem of Browning’s. At any rate, the exodus of the Rappites was followed by the disintegration of the Owenite settlement before it was hardly established in what was perhaps “a fatal atmosphere.” For instance, the germs of malaria had already been released. Our heroes are not, in fact, Rapp and Owen-but populations, inclusive of the Rappite hens and roosters who dwelt outside Utopia, inclusive of the community of drunks which built its citadel at the gates of Owenite Utopia, inclusive even of “the little goat who, in 1940, cried and cried with its fleece caught on a thorn bough.” All that remained of New Harmony, in 1940, was human nature and the spectre of two enchanting dreams which, Jehovah’s and Rousseau’s, could not pass away. An angel’s footprints in stone, the maze where the Rappites had wandered, the black locust trees which the Rappites had left standing as their most macabre monument. Of the Owenites, fewer relics, fewer monuments, since their contribution to society had to do with legislation and government in all nations. Of the Owenites, only the golden rain trees which were to cast their shadows over “a new moral world,” when there should be neither crime nor punishment- not one sentient creature crying. “Utopias of the past seemed, in spite of their shade trees, not so tangible, finally, as Miss Hobbie and Miss Duckie, old sisters carrying their feather pillows to the show where the seats were hard to set on-sneaking in to see Clark Gable. All mankind seemed not so real as one lonely, frostbitten character, like the man who died with his feet in the ashes of the cold stove last winter, or was it winter before last ?” People were still betting on imaginary horses-like those at the race track at Dade Park, like those of the Apocalypse, too. Roosevelt was a white man riding on a white horse. Hitler was a brown man riding on a brown horse.

In fact, the phantasmagoria of life persisted, above and beyond the crystalizations of lost Utopias.

Marguerite Young does not relate the dilemma of two Utopias for the sake of an easy maxim. Life is viewed in its irrational diversity, and no judgment is passed. The narrator of an epic, cosmic and psychic, she speaks and sings her tale, words and visions rising and falling with the rhythm of life, which has, she implies, more agents, seen and unseen, than can be mentioned in even this spacious contest. We must consider, for example, in considering New Harmony whether the whale swallowed Jonah or Jonah swallowed the whale-the effects of such translucent matter on the present fluctuation of Wall Street. We must consider the woman “who buried her baby, no bigger than her hand, in a hollow tree stump, filled with old cocoons and autumn leaves.” ‘When she came back next spring, they all were gone. From the shadows who people New Harmony in 1940, from “the walking dead,” rise, by subtle, implicit innuendo, the living shapes and voices of a still persistent past, bevies of kings, emperors, clowns, cotton lords, cotton workers. Human progress is shown in many shapes, through Father Rapp’s golden rose of Micah, to be enjoyed only by the dead, through Robert Owen’s toy pyramids which rep resented, he said, the edifice of human society at that date, his toy blocks which represented human society when it should be conducted according to the light of reason only. “Alas, however, for the best of plans! We are all, finally, perhaps the best of us, mistaken human beings, like our human life, which may be another mistake, due to the aboriginal whirlwind.” Father Rapp spent his old age as a million aire growing peach trees. Robert Owen spent his old age discoursing with those spirit voices whose existence he had previously denied, in arguments with Coleridge at Manchester.

Marguerite Young does not relate the dilemma of two Utopias for the sake of an easy maxim. Life is viewed in its irrational diversity, and no judgment is passed. The narrator of an epic, cosmic and psychic, she speaks and sings her tale, words and visions rising and falling with the rhythm of life, which has, she implies, more agents, seen and unseen, than can be mentioned in even this spacious contest. We must consider, for example, in considering New Harmony whether the whale swallowed Jonah or Jonah swallowed the whale-the effects of such translucent matter on the present fluctuation of Wall Street. We must consider the woman “who buried her baby, no bigger than her hand, in a hollow tree stump, filled with old cocoons and autumn leaves.” ‘When she came back next spring, they all were gone. From the shadows who people New Harmony in 1940, from “the walking dead,” rise, by subtle, implicit innuendo, the living shapes and voices of a still persistent past, bevies of kings, emperors, clowns, cotton lords, cotton workers. Human progress is shown in many shapes, through Father Rapp’s golden rose of Micah, to be enjoyed only by the dead, through Robert Owen’s toy pyramids which rep resented, he said, the edifice of human society at that date, his toy blocks which represented human society when it should be conducted according to the light of reason only. “Alas, however, for the best of plans! We are all, finally, perhaps the best of us, mistaken human beings, like our human life, which may be another mistake, due to the aboriginal whirlwind.” Father Rapp spent his old age as a million aire growing peach trees. Robert Owen spent his old age discoursing with those spirit voices whose existence he had previously denied, in arguments with Coleridge at Manchester.

The level of perpetual change is expressed in Indiana’s shifting landscape, one of many symbols. “For thousands of years, what is now the state of Indiana was a vast plain of granitic rock covered by a deep, salt, tideless sea.” When man arises at last, he is “already old and corrupt, like the earth before him-a creature with a history.” There was “never a first dawn”-“never a pristine Eden but that where the ants performed their marriage flight and lost their wings”-a statement which profoundly expresses the basic conception of the cost of life.In juxtaposition with the lost sea of Indiana, we witness moments no less ghostly, drawn from the largesse of time and space: old, deaf, blind, dreaming George III, playing a harpsichord or rather a series of harpsichords–or barking like a mad dog at Windsor; the unacknowledged death of Anne Bronte in a seaside hotel; the Pope of Rome dressed as the Pope’s valet and become, by this shift in costume, God’s truest representative on earth ; the fat Emperor of Russia, entertaining “a cancerous tutor or a ballet dancer from an other sphere,” Abraham Lincoln, Queen Victoria, Frances Wright, Audubon, Raffinesque, John Quincy Ada ms, Coleridge, Shelley, many other notables ; indeed, many disrelated people and events drawn into a complex system which seems, in each instant, unity.

The level of perpetual change is expressed in Indiana’s shifting landscape, one of many symbols. “For thousands of years, what is now the state of Indiana was a vast plain of granitic rock covered by a deep, salt, tideless sea.” When man arises at last, he is “already old and corrupt, like the earth before him-a creature with a history.” There was “never a first dawn”-“never a pristine Eden but that where the ants performed their marriage flight and lost their wings”-a statement which profoundly expresses the basic conception of the cost of life.In juxtaposition with the lost sea of Indiana, we witness moments no less ghostly, drawn from the largesse of time and space: old, deaf, blind, dreaming George III, playing a harpsichord or rather a series of harpsichords–or barking like a mad dog at Windsor; the unacknowledged death of Anne Bronte in a seaside hotel; the Pope of Rome dressed as the Pope’s valet and become, by this shift in costume, God’s truest representative on earth ; the fat Emperor of Russia, entertaining “a cancerous tutor or a ballet dancer from an other sphere,” Abraham Lincoln, Queen Victoria, Frances Wright, Audubon, Raffinesque, John Quincy Ada ms, Coleridge, Shelley, many other notables ; indeed, many disrelated people and events drawn into a complex system which seems, in each instant, unity.

Values fluctuate; effects may precede cause; there is the fact of chaos, negative and positive. There is always a question mark and what Margueri te Young calls “a joker in the philosophic pack.” She does not see life as, in fact, a given system. Yet by doubting each accepted value, each norm, each convention, by examining the fragments and splinters, she creates out of a manifold diversity of impressions and artistic unity, a roundness of strange beauty, a most distinguished work of art. Her vision is, for all its strangeness, not willfully solipsistic, the refuge of an unfounded individualism. As evidenced by her poetry, lmmoderate Fable, a fable moderate because it omits narcissism, her thinking has been conditioned by philosophers Democritus, for example, Locke, William James, many others to whom she makes, indeed, a constant though unobtrusive reference. Fewer idealists than skeptics. She has humanized, however, the unhuman fable. What may in Angel in the Forest appear to the unschooled or biased reader a singular display of mental acrobatics for their own sake must seem, to the schooled, the generous, the end-result of amoral mental discipline. Only an artist of her stature can afford to clothe her keen, realistic, nudist deductions in the glittering brocades of such a baroque, unreal, out-of-this-world fantasy. She philosophizes with her tongue in her cheek.

Values fluctuate; effects may precede cause; there is the fact of chaos, negative and positive. There is always a question mark and what Margueri te Young calls “a joker in the philosophic pack.” She does not see life as, in fact, a given system. Yet by doubting each accepted value, each norm, each convention, by examining the fragments and splinters, she creates out of a manifold diversity of impressions and artistic unity, a roundness of strange beauty, a most distinguished work of art. Her vision is, for all its strangeness, not willfully solipsistic, the refuge of an unfounded individualism. As evidenced by her poetry, lmmoderate Fable, a fable moderate because it omits narcissism, her thinking has been conditioned by philosophers Democritus, for example, Locke, William James, many others to whom she makes, indeed, a constant though unobtrusive reference. Fewer idealists than skeptics. She has humanized, however, the unhuman fable. What may in Angel in the Forest appear to the unschooled or biased reader a singular display of mental acrobatics for their own sake must seem, to the schooled, the generous, the end-result of amoral mental discipline. Only an artist of her stature can afford to clothe her keen, realistic, nudist deductions in the glittering brocades of such a baroque, unreal, out-of-this-world fantasy. She philosophizes with her tongue in her cheek.

To combine cold, unsentimental thinking with quick, lively tragicomedy, the commonplace like the old outhouse with beautifully mad imagery like “the asexual angel Gabriel in a hop field”-therein lies the genius of the adventuresome performance. The book is, as so many critics have pointed out, “wild,” perhaps because made up of “wild” data, angels, drunks. The writing seems free of literary scheming, too, as if the writer needed no sly skill. Readers looking for neatly swept sidewalks, road signs, traffic lights, will find themselves engulfed in a precolonial wilderness, a fertile abundance of many-faced trees and flowers-in the hollow of every tree, a man, on every treetop, an angel. If there is in Miss Young’s book a “too much,” as the more literal minded may argue, it is the “too-much” of the Renaissance imagination which delighted in excesses, the “too much” of a modernist Rabelais, a John Webster. The writing, from first to last, shows a dynamic force, stronger than the neat rules of literary perfection. ‘It is a piece of banal, sacred life, not anemic. (And some of our most gifted writers suffer from anemia, perhaps because they have made the mistake of worshiping perfection, the one thing never worshiped by Marguerite Young, who writes: “Our perfection is our death.”)

To combine cold, unsentimental thinking with quick, lively tragicomedy, the commonplace like the old outhouse with beautifully mad imagery like “the asexual angel Gabriel in a hop field”-therein lies the genius of the adventuresome performance. The book is, as so many critics have pointed out, “wild,” perhaps because made up of “wild” data, angels, drunks. The writing seems free of literary scheming, too, as if the writer needed no sly skill. Readers looking for neatly swept sidewalks, road signs, traffic lights, will find themselves engulfed in a precolonial wilderness, a fertile abundance of many-faced trees and flowers-in the hollow of every tree, a man, on every treetop, an angel. If there is in Miss Young’s book a “too much,” as the more literal minded may argue, it is the “too-much” of the Renaissance imagination which delighted in excesses, the “too much” of a modernist Rabelais, a John Webster. The writing, from first to last, shows a dynamic force, stronger than the neat rules of literary perfection. ‘It is a piece of banal, sacred life, not anemic. (And some of our most gifted writers suffer from anemia, perhaps because they have made the mistake of worshiping perfection, the one thing never worshiped by Marguerite Young, who writes: “Our perfection is our death.”)

It is just because of its unusual range of experience that Angel in the Forest may appeal to many diverse readers as Utopia, as mock Biblical, as Americana, as essay on human character. The book is too vivacious to be written down as “rare,” for the few only. Nothing is here esoteric or invented for the sake of invention. Every figure is human or the project of the human imagination, of the greatest con sequence in ordinary life, partaking, too, of that life. As to the angel Gabriel, for example (and he is another barefoot boy on Wall Street)-

It is just because of its unusual range of experience that Angel in the Forest may appeal to many diverse readers as Utopia, as mock Biblical, as Americana, as essay on human character. The book is too vivacious to be written down as “rare,” for the few only. Nothing is here esoteric or invented for the sake of invention. Every figure is human or the project of the human imagination, of the greatest con sequence in ordinary life, partaking, too, of that life. As to the angel Gabriel, for example (and he is another barefoot boy on Wall Street)-

Evolved out of ether and air, tears and sorrow, an angel stood in the hop field. He was big, massive, corpulent. He carried a rainbow on his back . . . . He was taller than an oak full grown, and of a diameter exceeding the oak, the beech, the sassafras. . . . He was grass and fire and homely as an old shoe. He was a farmer with a golden book in his hand. . . . His voice was like the river Wabash, loud and wild, rolling between the buff-colored hills.

Perhaps Miss Young agrees, to some extent, with the crucial angel she despises. Like Voltaire in Candide, like Dr. Johnson in Rasselas, she affirms that this is not the best of all possible worlds, that there is no perfect happiness attainable. Yet even this formula fails-for it is Shelley’s bright hair, the ghost of Shelley, Robert Owen’s friend, who rides in the wind with Robert Owen on his last journey of man’s redemption from crime and punishment. Perhaps the drama is still going on?

Indeed, it is a very grim fairy tale Marguerite Young has written grim and glorious.

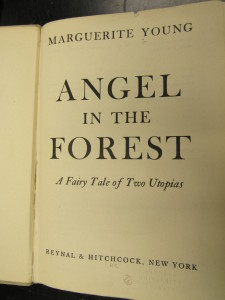

ANGEL IN THE FOREST: A FAIRY TALE OF TWO UTOPIAS.

By Marguerite Young.

Reynal and Hitchcock. 313 pages. 1945. $3.00.