PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAEL KIRCHBERGER

Marianne Hauser was Anais Nin’s neighbor in New York. They lived at 2 Washington Square, a high rise apartment complex located south of Washington Square Park, and saw each other when Nin was in town, that is, when she wasn’t living in California with her west coast husband, actor Rupert Pole. Her east coast husband, Hugh Parker Guiler, also known as Ian Hugo, whom she lived with in Paris, was an artist, a film maker and print maker. Hauser got her apartment from her old friend Ruth Stephan. Stephan was publisher of the avant-garde art journal The Tiger’s Eye (1947-1949), a publication which featured Guiler’s prints and stories by Nin, Hauser and Marguerite Young, who was also the fiction editor.

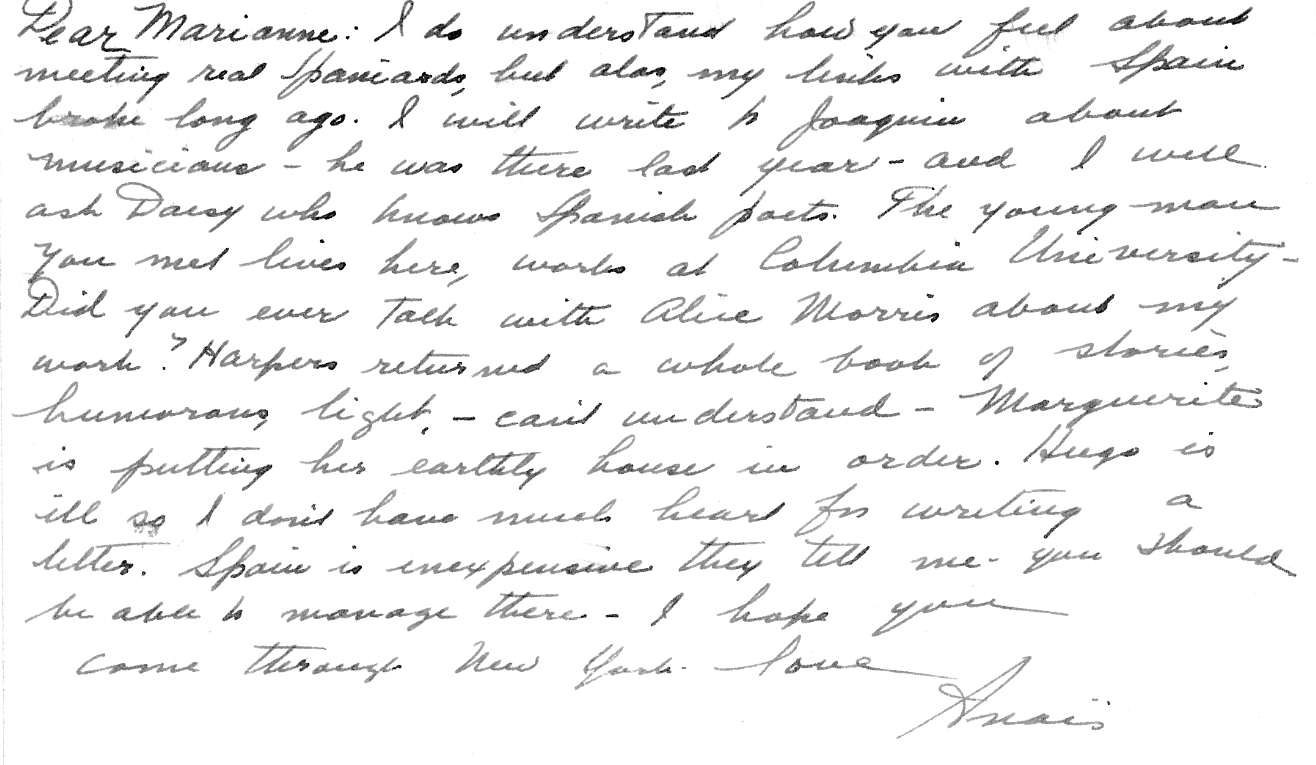

It’s not really possible for me to say how Nin and Hauser met, when or where. It could have been in Paris in the 30s, New York in the 40s, 50s, or 60s. Material Michael Kirchberger scanned for me makes it possible to say it was long before the 1970s. Whenever it was they found time to go to the beach together. Nin and Hauser were not necessarily good personal friends, but they were certainly artistic allies, and shared many connections beyond Marguerite Young and Ruth Stephan. Nin never failed to mention Hauser when asked for the names of important writers. I have viewed this relationship through this lens, of a more prominent author (Nin) promoting the work of a less known, neglected one (Hauser). Nin is tirelessly generous. But there is evidence that earlier on Nin was asking Hauser for help placing a book of short stories (see the scanned, undated letter).

Their relationship in print begins with The New Novel (Macmillan, New York, 1968), a book published by Nin in 1968. The final chapters of this book were first published in the inaugural issue of the literary journal Studies in the 20th Century (Russel Sage College, Spring 1968, edited by Stephen H. Cooke). Nin begins by saying she never intended to write any literary criticism, and then goes on to detail the difficulty she had getting her work published in the early forties, which she attributed to a general American hostility towards avant-garde European writing, particularly surrealism. Americans divided literature into realist and anti-realist schools, preferring the latter, whereas Europeans accepted a broader range of aesthetic practices. In the book she lays out a case for writers like Kafka, Joyce, Artaud, Proust, Stein etc. Hauser is mentioned in connection with Djuna Barnes and Anna Kavan, as well as Marguerite Young, whose Miss Macintosh My Darling had appeared two years previously. The comparisons are apt, as both havemany things in common with Hauser, but there are major differences as well, especially with Anna Kavan. Another writer mentioned by Nin is Isabel Bolton, another neglected writer of New York in the 40s who (like dawn Powell) has enjoyed a major revival of interest, if not sales. Nin writes of Hauser:

“A writer of exceptional style and subtlety is Marianne Hauser. When people will tire of noise, crassness, and vulgarity, they will hear the truly contemporary complexities of Marianne Hauser’s superimpositions. A new generation trained to imagery by the film may appreciate her offbeat characters and skill in portraying the uncommon.”

She then quotes The Other Side of the River, her O’Henry Prize story of 1948 (The Other Side of the River. Mademoiselle, (April 1948). Reprinted in Brickell, Herschel. 1948. Prize stories of 1948: the O. Henry Awards. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. Collected in A Lesson In Music. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964. And The Collected Short Fiction of Marianne Hauser. Normal [Ill.]: FC2, 2004.), and mentions the 3 novels she had published in English at that point, Dark Dominion, The Choir Invisible, and Prince Ishmael.

Hauser returned the favor in Issue 2 of Studies in the 20th Century (Fall, 1968) with her piece, Anais Nin: Myth and Reality. The occasion is the publication of the first two volumes of Nin’s diary. When Hauser describes Nin she could be describing herself:

“…the very nature of her genius resists classification. She does not belong to a school. Strictly speaking, she does not even belong to one nationality. Born in France, of Spanish father, a Danish mother; long time resident of Paris; vagabond traveler; naturalized citizen of the United States: her roots grow from many cultures. Wherever she goes she creates her own international climate.”

Similarly with the style:

“Deterioration merges with glamor. The present flows into the past. Anais Nin’s concept of time is Bergson’s duree reelle—a phenomenon of the mind.”

Hauser mentions Otto Rank, the psychoanalyst Nin famously had an affair with, and whom Hauser also knew. In volume 7 of the diary Nin writes:

“Notes on Marianne Hauser [:] Sent to US in 1937 as a columnist by a Swiss newspaper. Has been here ever since. During this period she has been patiently refining the remarkable prose style of Dark Dominion….She knew Rank and was analyzed”

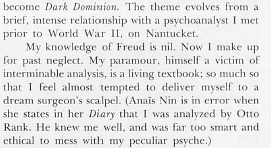

Hauser disputes this in About My Life So Far:

Hauser never mentions psychoanalysis without palpable contempt. Thomas Spine, the psychiatrist in Dark Dominion, engages the reader’s pity at times, but he is a shallow rationalist with no personal insight. His relationship with his wife is parasitic. He is a sexless, Lawrencian head. Forty years later her Mr. Ashley repeatedly and explosively derides psychoanalysis. What she is attacking is the culture of therapy and the cultic, totalizing tendency of Freud and Freudians. Psychoanalysis in Dark Dominion destroys souls and is opposed to the imagination. It is the ultimate illusion, imprisoning human beings in a normative, ego driven sexuality and conformity. Nin and Hauser experience Rank as the opposite of this, a psychiatrist dedicated to the freeing of the creative imagination.

In 1971 Nin wrote a much more extended piece on Hauser for the book Rediscoveries (Crown Publishers, New York, 1971; some of the essays have been published online as people rediscover the authors rediscovered 45 years ago!), centered on A Lesson in Music, her short story collection of 1964:

“In the opening paragraph of Marianne Hauser’s book of short stories one becomes aware that a fine precision instrument has chiseled this prose, enabling to create physical and emotional portraits that have a crystalline transparency of image and meaning. The simplest of beginnings leads one into past, present and future, and a care for detail evokes the most variegated atmospheres. The interrelation between the outer and inner worlds of men and women, between dreaming and waking action is carefully balanced. The movements of love and hatred, espousal of and recoil from experience are faithfully delineated and made perceptible. Marianne Hauser achieves sensitivity without sentimentality, irony without loss of humanity.” (p. 116)

The essay discusses each of the stories and concludes with two paragraphs of description and praise. Nin, like everyone else who tries to describe Hauser’s work, has to somehow convey its anti-realist properties, which exist alongside an extremely precise prose of visual description and emotional nuance. Nin continues to champion Hauser in interviews, like this one for an oral history:

There is no evidence that Hauser sought in any way to exploit her friendship with her much more famous neighbor. When I asked Michael if Hauser was irritated either by Nin’s interest in women’s writing as a category, or by her fame he said his mother was very forgiving towards her friends. Nin and Hauser were both feminists of course, but neither were post-modern, and neither viewed sexuality or gender through the lenses of later generations, even though the only serious critical work on Hauser has been on The Talking Room and has been explicit in its association of her radical style with issues of gender and sexuality, a connection Hauser would have rejected out of hand. Not so Nin. Nin was very involved at the end of her life in women’s issues. She discusses gender and art extensively in a radio interview hosted by Charles Ruas, The Female Angst. One of Hauser’s colleagues at Queens College, poet Harriet Zinnes (a friend of both Nin and Hauser) wrote about this in an essay on Nin for the book Anais Nin: Literary Perspectives (Suzanne Nalbantian ed., St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1997):

“Adam Begley…defined rather crisply what he called ‘postmodernists’ notion of the self’ as a ‘fractured entity composed of socially constructed attitudes’. How unlike the conception of the self of Anais Nin. To Nin, the self is authentic only as it expresses that ‘city of the interior’, and in the real world of the diaries and the fleeting, wavering, shaped world of her fiction, the self, hardly postmodern, is not socially constructed, not fractured at all but a coherent home, a hearth, a womb of the senses. But this interiority is built on a trust in a reality and is essentially the consequence of an acceptance of outward experience that is transformed as it turns inward. That transformation is never made dull in Nin’s work by passivity. Nin builds architectonically from the dream outward. It is as if her fiction is built upon dialect, a tension between the outer and inner worlds. How unlike the Maoist psychoanalyst and semiotician of desire, the French Julia Kristeva, who, in her novel The Samurai, looks for ‘the calm safety of classical architecture and the rare equilibrium that transmutes geometry and happiness’….Of her own work, Nin declares in The Novel of the Future, ‘the external story is what I consider unreal’.”

Kristeva figures prominently in Andrea Harris’s analysis of The Talking Room (Other Sexes: Rewriting Difference from Woolf to Winterson, SUNY Press, 1999). Of Hauser and Nin, Zinnes quotes The New Novel and writes:

“The novelists of violence, Nin believes, of gutter language, use shock instead of feeling, dead language instead of the living rhythms of language, which is itself a form of magic and transformation. In her Novel of the Future, Nin quotes…Hauser to show that [she has] dwelled ‘on the pursuit of the hidden self’, [has] dramatized the conflict between the conscious and unconscious self to produce greater authenticity, an ‘emotional reality’….Marianne Hauser, a friend of Nin and author of Prince Ishmael and The Talking Room, in a brilliant story called ‘The Seersucker Suit’ illustrates what Nin means by ‘emotional reality’ in fiction. Hauser reveals the terror and loneliness of urban life through the symbolism of the magic birth of a dog-son from a mangy bit of old fur….Nin felt that Hauser’s writing acknowledged the truths of psychoanalysis, which, in the writing of fiction, required the novelist no longer to adhere to the old notions of a progressive plot, resolution, climax and development of character. Our desires are as much a reality as our throwing ourselves exhausted on the bed when we return from work. A scrap of fur becomes a child. This is not a literal transformation. It is the discovery of ‘reality by discarding realism’. It is the symbolic equation that the reader understands—because, as Nin makes clear in her critical writing and implicitly in her diaries, the self’s desires are nakedly the same for us all.”

Of course, The Talking Room and much of what she wrote afterwards is marked by verbal violence and shock. It is also difficult to reconcile what ‘psychoanalysis’ can possibly mean in this context. Like ‘communism’ or Christianity, psychoanalysis is not a monolith, and what artists like Nin and Hauser, deeply influenced by European thought and aesthetics, take from it has little to do with talk therapy and pat explanations of reality.

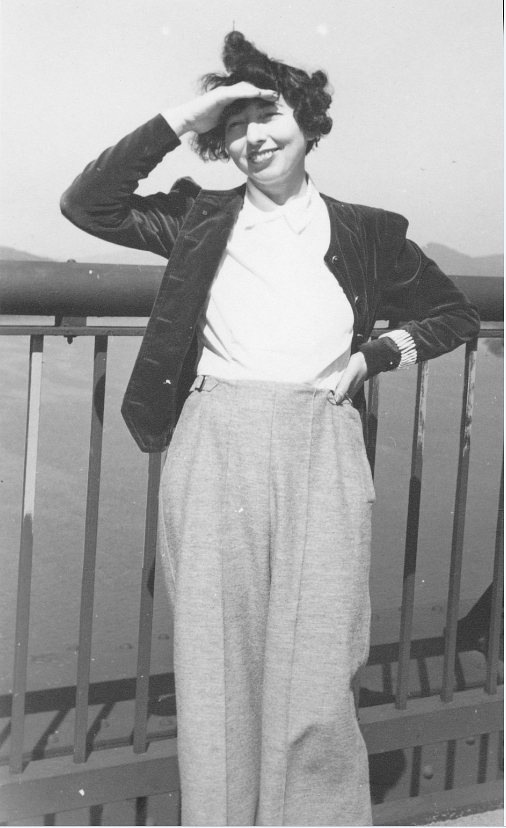

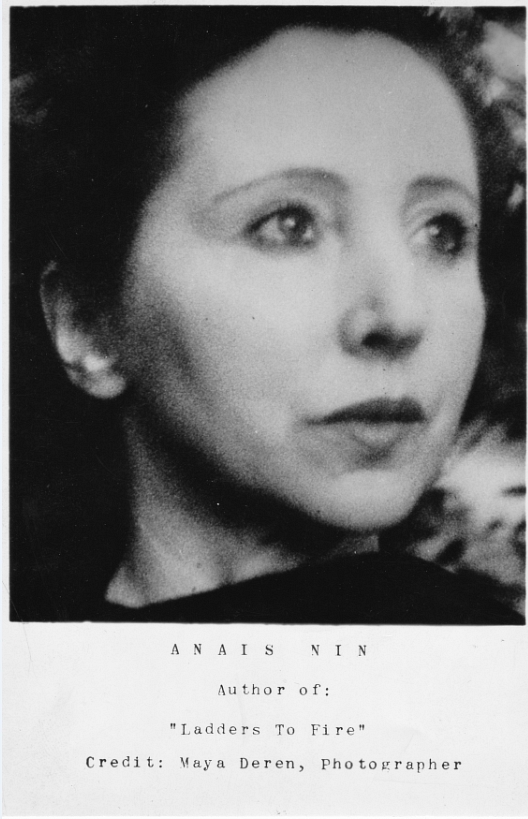

Zinnes met Nin in 1961, when she wrote a good review of Seductions of the Minotaur. Later, Nin suggested Zinnes review Prince Ishmael (1963) which led to their friendship. (Zinnes, in Recollections of Anais Nin, Benjamin Franklin ed., Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio, 1996). This might when Nin sent this postcard to Hauser, with a photograph of Nin taken by Maya Deren:

On the flip side is a note written to Hauser by Nin asking her help in placing a collection of short stories with ‘Harper’s’. Hauser had been publishing Harper’s Bazaar for years. The card is undated. She asks Hauser to visit when she next passes through New York. Hauser lived in New York City from 1937-1947, 1957-1959, and from 1966 until her death in 2006.