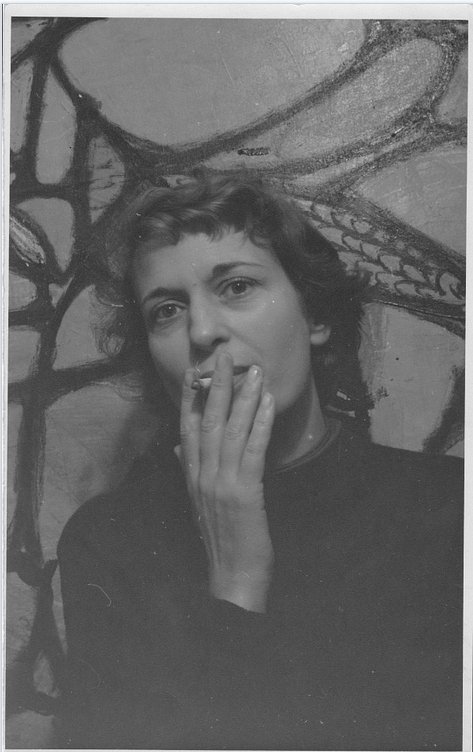

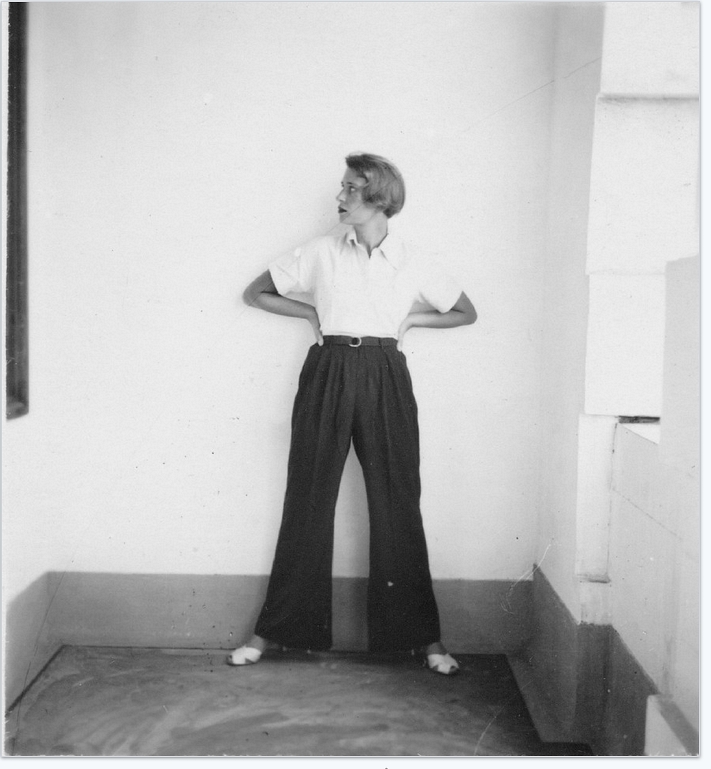

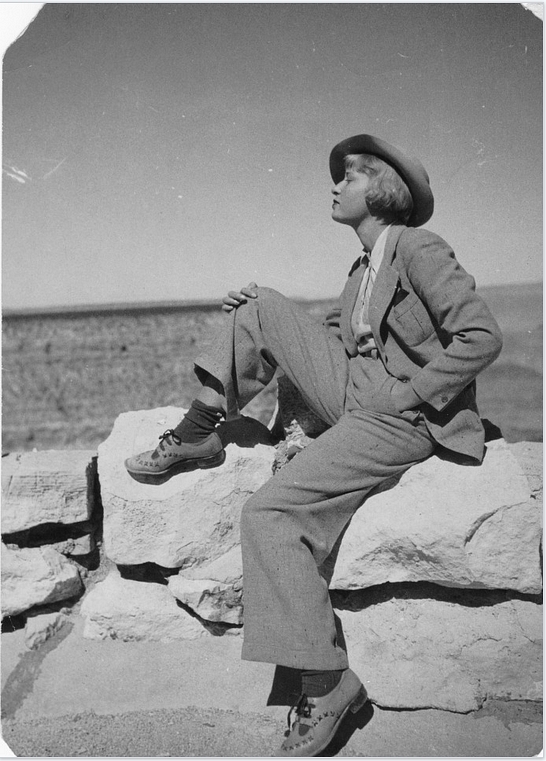

Recently I spent 3 days in San Francisco and had an opportunity to visit with Marianne Hauser’s son, Michael. Most of Hauser’s papers are housed in the archive at the University of Florida, but Michael has boxes of photographs and some letters. He was kind enough to share them with me, and has been scanning material for me to post. Without Michael this whole crazy thing would have been much more difficult, even impossible. Most everyone who knew Hauser has died, and those living have scattered, imperfect memories, as do I. So it is great to be able to open a letter and confirm that so and so was her agent for such and such book, that editors who rejected Prince Ishmael were brokenhearted. Letters are going to be the backbone of this story, and most of them are sitting in Florida. But these were not. San Francisco is the only city outside of New York I can truly say I love. So visiting Michael is no hardship at all. My publisher Miette joined us for lunch. We hiked up an arid hill and watched F-14 fighter jets wack off in the stratosphere. And Michael and I talked.

One thing that came up, as it often does, is Marianne’s hostility to any kind of identity politics. She was Alsatian, certainly, but she was an author first and foremost and not a hyphenated one. Because I was in town to give a reading, I also saw an old friend who has run an alternative press for 30 years. She told me she participated in a LGBT panel to discuss LGBT issues in publishing. For years she has been a remarkably supportive publisher for that community. It has not been her exclusive work but work she is passionate about. At the conference it was discovered by other participants that she was a heterosexual. She never claimed otherwise, of course. She felt it was irrelevant. But some conference organizers and participants did not feel that way and ostracized her, despite decades of publishing gay, bi and trans authors, that is, putting her money where her mouth is. A friend later informed her that probably they felt like she had occupied a seat that could be occupied by a homosexual. I guess some chairs would rather be smothered by gay butt. She said that in the course of this conference it came up that many gay men don’t like it when straight women write from the point of view of a gay man. I said that straight women have more insight into the experiences of gay men than straight men do, and the women laughed. Most women have sucked a lot of dick, after all, and had boyfriends who were assholes. Seriously though, our emotional lives converge even where our experiences differ. Hauser spoke very forcefully against this kind of stupidity, as the previous post shows.

Hauser knew many artists, many of them gay, and spent summers on Monhegan Island, Maine. One of these artists was William Kienbusch. Her last novel, Shoot Out with Father, was inspired by the relationship between Bill and his father. There are many letters written by Bill to Marianne.

Hauser did not believe it was right to use the artist’s life to explain her creations. But she did draw extensively on her life, as all novelists do. Once it becomes writing, art, it ceases to be about the life. The life is a starting point, and imagination takes over. Michael and I discussed how to honor this. I guess a corollary is, if an artist does significant work, and has an interesting life, and is no longer alive and able to control that situation, then in a sense it becomes fair game. Life may not explain the work, but it can contextualize it, while the work might fill in details of the life where the record of letters and memories do not. It is not that life happened in the way the plot of the novel does, but rather, the novel dramatizes the emotional situations of life. Life and work are really inseparable, and each can illuminate the other.

Thank you so much for your research on my old friend and teacher, Marianne. The photos are precious treasure! I just came across my autographed copy of Prince Ishmael and thought of her and Alice Morris, who was also my teacher for one class at the New School. I have wonderful memories of spending time with Marianne in NYC.

Dear Jon,

I do hope this finds you keeping well during this strange time; and hello from sunny London. I write from Faber in London, where I oversee our Classics publishing, as I have been exploring the possibility of reissuing novels by Marianne Hauser. I believe you are something of an expert, judging by this incredible website, and wondered if you might be kind enough to discuss this possibility together further? Thank you so much for any advice you can offer, and wishing you all the best.

Very best, Ella

I sent you an email. Would LOVE to discuss anything to do with Marianne Hauser.

Jon