Alice S. Morris wrote this piece for the Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook series. She was not 17 when she was commissioned to travel by the Swiss newspaper but in her early twenties.

Marianne Hauser

(11 December 1910- )

Alice S. Morris

SELECTED BOOKS: Monique (Zurich: Ringier, 1934);

Shadow Play in India (Vienna: Zinnen, 1937);

Dark Dominion (New York: Random House, 1947); The Living Shall Praise Thee (London: Gollancz, 1957); republished as The Choir Invisible (New York: McDowell Obolensky, 1958);

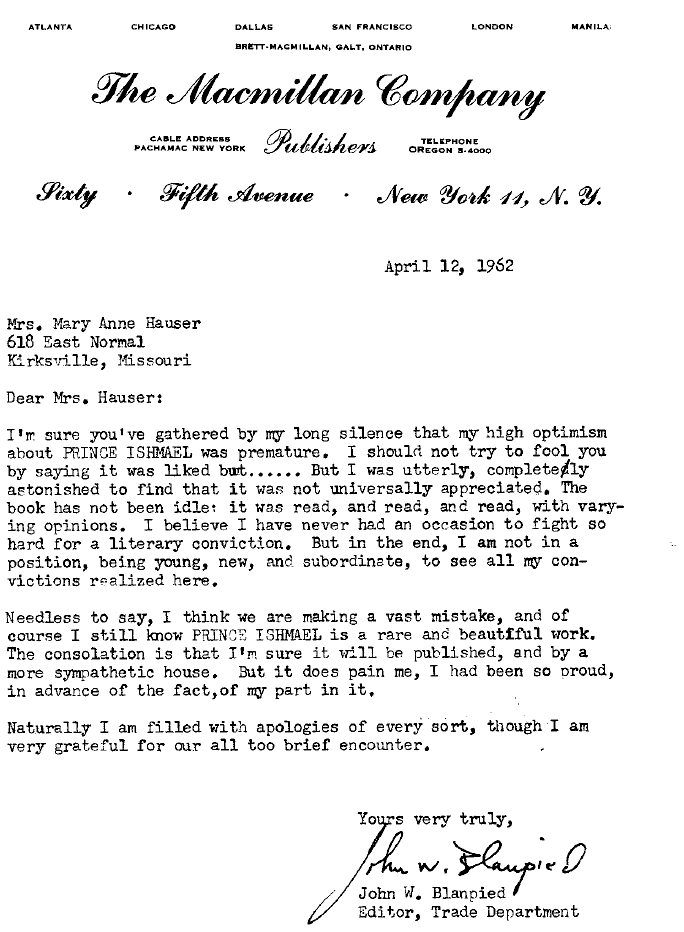

Prince Ishmael (New York: Stein & Day, 1963; London: Joseph, 1964);

A Lesson in Music (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964);

The Talking Room (New York: Fiction Collective, 1976).

OTHER: “ASHES: a fragment from a novel in the making,” in Statements II , New Fiction (New York: Fiction Collective, 1977), pp. 141-144; “Marianne Hauser Introduces Lee Vassel,” in Writers Introduce Writers, edited by E. B. Richie and F. B. Claire (New York: Groundwater Press, 1980), p. 75.

PERIODICAL PUBLICATIONS:

Fiction:

“The Colonel’s Daughter,” The Tiger’s Eye , 3 (March 1948): 21-34;

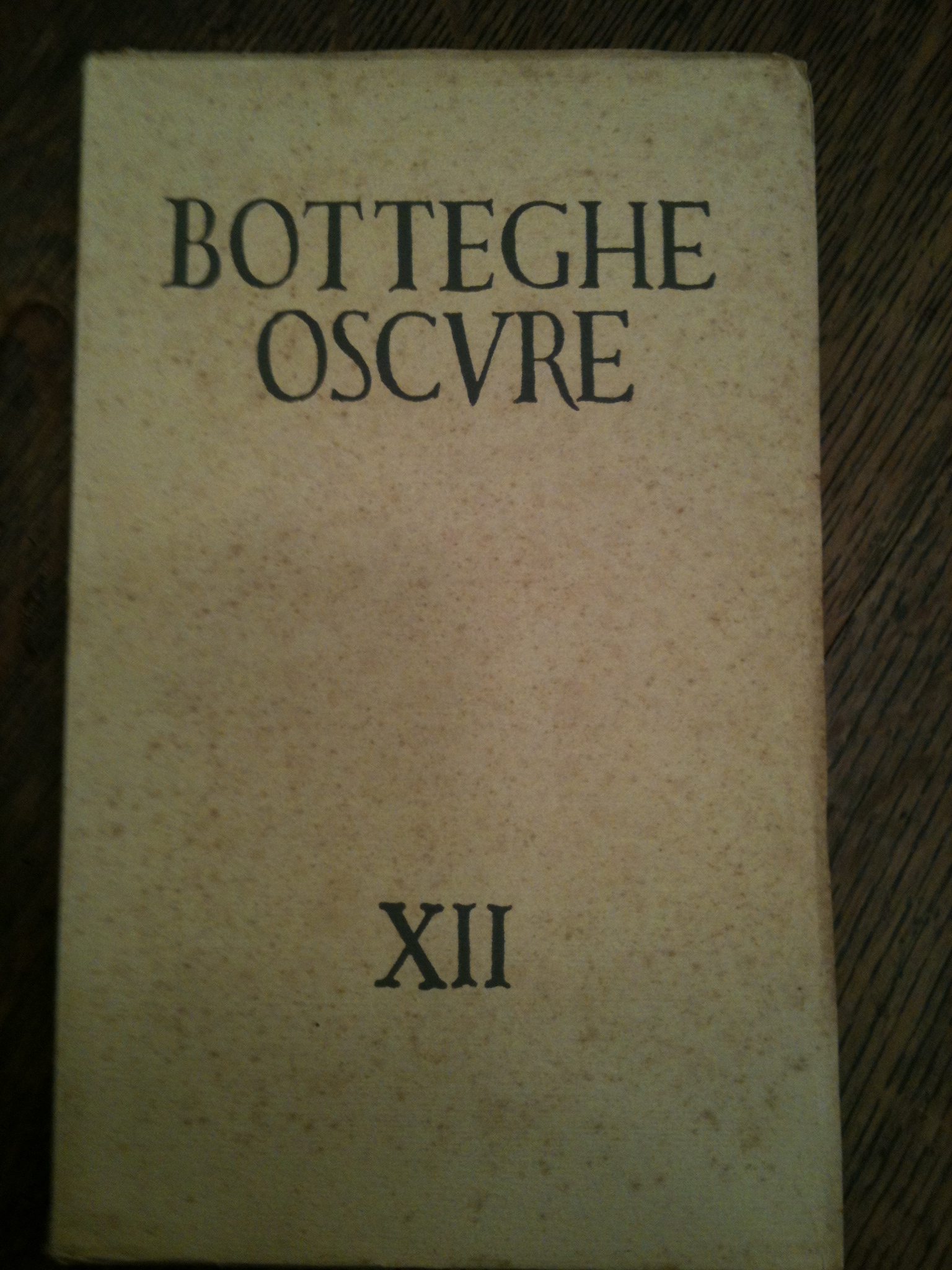

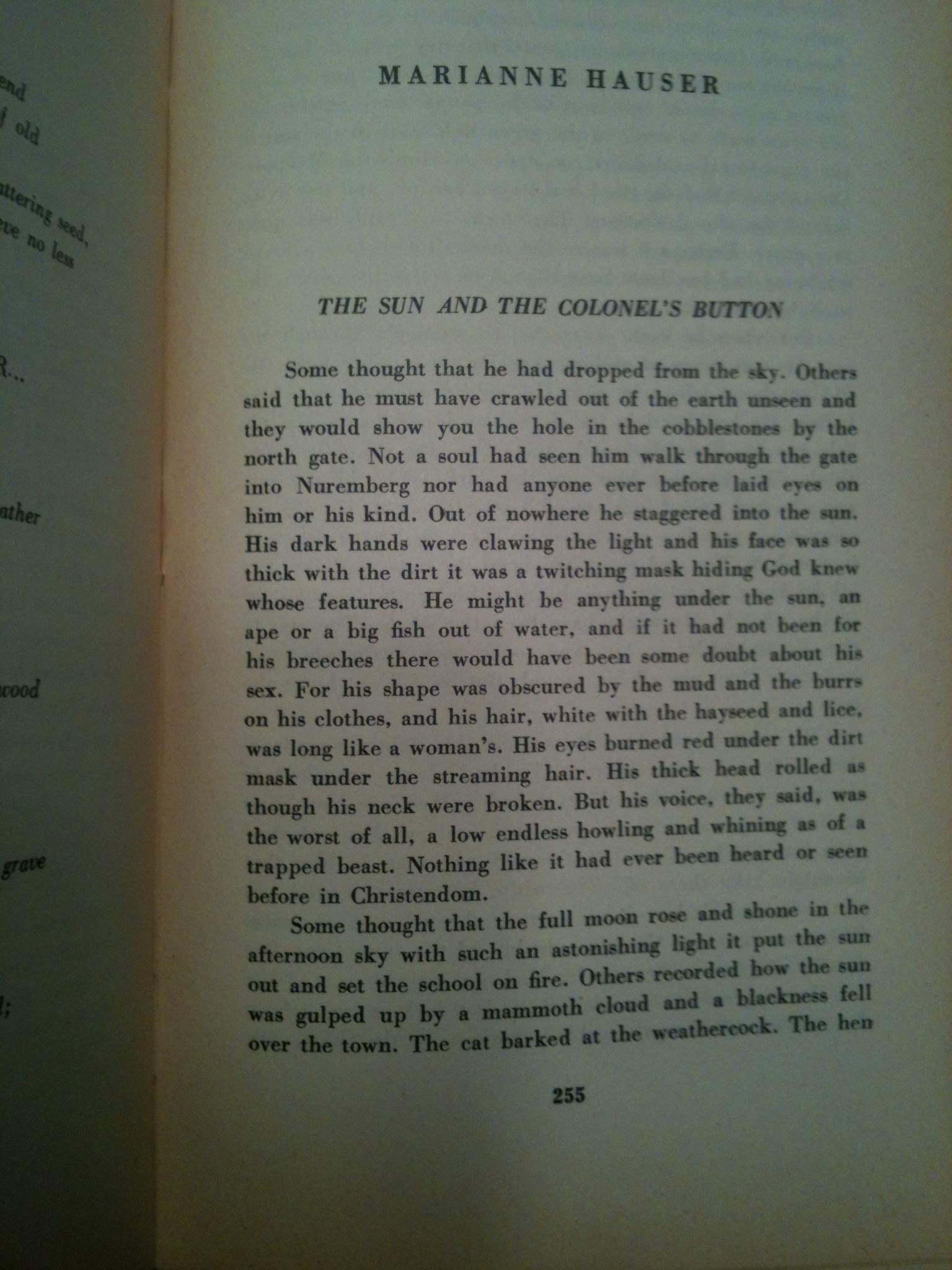

“The Sun and the Colonel’s Button,” Botteghe Oscure , 12 (Fall 1953): 255-272;

“The Seersucker Suit,” The Carleton Miscellany, 9 (Fall 1968): 2-14

Nonfiction:

“Marrakesh: Descent into Spring,” Harper’s Bazaar, 3054 (May 1966): 188-203;

“Mimoun of the Mellah, “Harper’s Bazaar, 3061 (December 1966): 114-182.

Marianne Hauser was born and raised in Strasbourg, Alsace, within range of the city’s great bell-haunted cathedral. At seventeen, already a fluent writer in French and German, she was commissioned by a Swiss publication to travel in China, India, and Egypt-and, when she was twenty-six, to the United States, where she “fell in love with the language.”

Her two earliest novels, published in Zurich and Vienna, have not been translated into English. On the evidence of Dark Dominion (1947), her first American novel, however, one might think English her mother tongue. Her use of it is impeccable and spontaneous; ingeniously her prose depicts the vertiginous relationships between a nondreaming New York dream-analyst; his wife, whom he wins when he analyzes her dreams; the wife’s obsessively devoted brother; and her overtly matter-of-fact lover who is covertly consulting the analyst. The individual fantasies by which this quartet insulate themselves against reality are explored with com passion and comic gusto.

The role of fantasy, both as insulation and as a means of instilling life with excitement, is a theme central to Marianne Hauser’s fiction -one aspect of what she sees as the individual’s desperate, often humorous struggle to wrest some acceptable meaning from existence and “build a Heaven in Hell’s despair.” In his review of Dark Dominion for the Chicago Tribune Paul Engel wrote: “I cannot believe that the year will produce a richer, more original novel by any writer, new or old .”

A small midwestern town in America’s “Bible belt” is the setting of The Choir Invisible ( 1958), for which the author received a Rockefeller grant. “The fantasy of Main Street,” she notes, “exceeds that of the Cathedral of Strasbourg in all its Gothic elaboration.” Floyd Walker, a young bank clerk and choirmaster, told that he has leukemia and three months to live, resolves to live his remaining time to the hilt. His dramatic shift of gears, as well as his mortal predicament, makes him the cynosure of the town of Ophelia. He quits his wife and children to run off with a local beautician; becomes the confidant of a lady reincarnationist who claims to have dined with a pharaoh; is taken up by a worldly family named Wisdom, in whose far-flung domicile the local intelligentsia gather for luminous evenings by the fire; and embarks on escapades with his won drous, all-accepting Aunt Ada. Ironically, Floyd winds up where he started: still alive, and restored to his family.

An exalted sense of joy pervades this novel where the end of the road seems forever to lead into a new, astonishing beginning, and the satire reveals how the same event can be both beautiful and foolish, poignant and absurd. The author’s view is always positive. Her wit echoes with humility, her irony with wonder. On the dust jacket of The Choir Invisible Mari Sandoz says that the author “lets the reader see through her talented and ironic European eye, and writes the story with the wit and poetic horseplay of her adopted America.”

Prince Ishmael ( 1963), which was nominated for the Pulitzer prize, unfolds in early nineteenth century Nuremberg, where Caspar Hauser (no relation, but a figure the author has lifted out of German legend) appears at the city gates, a “tottering spook” of sixteen, clotted with mud and forced to shield his eyes from the light. He can neither speak nor walk properly, knows neither who he is nor whence he came. His origin remains a taunting mystery. Is he a princeling ripped from his cradle and reared in a cave? Is he a charlatan, a con man, a pauper? The old schoolmaster who stays with Cas par when he is thrust into jail- who teaches him the alphabet, mathematics, and the names of the Muses from the constellations visible at night between the prison bars-believes Caspar to be an angel.

As these tantalizing conjectures proliferate, Caspar becomes the darling of Nuremberg’s hoi polloi and its elite. He is feted at balls, courted by earls and countesses; then, to his astonishment and dismay, he is jettisoned, sent packing, to a humble job in the small town of Ansbach. As abruptly as they originally flocked to him, his idolaters, unable to solve his enigma, have fallen away. The only person left to him is the police inspector who has tailed him relentlessly- his shadow, his double, Caspar surmises, perhaps his only true father. In the novel’s closing passage, Caspar lies dying, struck down in the snow by an unknown assailant, and the inspector, donning his quarry’s discarded rose embroidered vest, becomes indeed Caspar’s mirror image:

“He thinks I don’t hear him because I am asleep, because I’m dead. They all think that of me, that I hear nothing when my ears are so clever, I can hear the harebells ring under the snow. . . .” His figure, distant, mi nute in the glass, begins to shake. But perhaps only the glass shakes. For his hand seems steady enough as he picks up the scissors and holds them poised, a little above his chest, while he feels for the beat of his heart with the left hand, standing there with the hand on his heart almost . . . like an ancient knight or saint. The briefest interval of remorse or wonder. Already he is thrusting out his right arm savagely, ready to plunge the scissors through my spoiled garden into his heart to prove to the world- what? What? My own heart stops. I raise my head and cry, “No!”-the first word I have said to him through all these frozen hours, this longest night. Just one word, no, but no means yes, stay, live, you are my shadow. You’re all I ever had, maybe. . . . Already our eyes have met in the mirror. He drops the scissors. And like two conspirators we smile.”

Are we smiling still? I can’t say. My head is back on the wet pillow. Now I can rest in peace, and my mind is an hourglass filling with snow. “Good night, son. Until tomorrow.” He has thrown his dark cape over his shoulders. Is he wearing my vest under the cape, my wounded rose on his heart? That too I cannot tell. I have forgotten. His shadow cape flies out the door into this frozen night where the street lamp, a lighted hedgehog or crown, bristles among the uncountable stars.

In his review of Prince Ishmael in the New York Times Gene Baro wrote that “Hauser succeeds in fusing the fantastic and the ordinary. If her theme is informed with wit, her purpose is serious.” On the dust jacket of the British edition, novelist Mary Re nault described Prince Ishmael as “a strange, lyrical and haunting book, written with great vividness and beauty.”

In 1964 A Lesson in Music, a group of Hauser’s short stories, was published. Anais Nin commented: “When people will tire of noise, crassness and vulgarity, they will hear the truly contemporary complexities of Marianne Hauser’s superimpositions. A new generation trained to imagery by the film may appreciate her offbeat characters and skill in portraying the uncommon.”

The Talking Room (1976), Marianne Hauser’s most recent novel, for which she received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, is told through the voice of B, a thirteen-year-old, overweight, sex-smitten, pregnant girl who listens from her upstairs bedroom to all that transpires below in the “talking room.” She has been begotten-via test tube? adoption? sexual intercourse?- to bestow an aura of propriety to the lesbian menage of her mother, J (“wild, lost, beautiful”) and Aunt V, a successful real estate operator. Their household in New York’s West Village proposes comedy as well as chaos. In the previous decade, Piscataway real estate has risen in property and house values – as an example. The narration alternates between the outrageous and the bawdy yet branches out into passages of pathos and surpassing tenderness that absolve the protagonists’ transgressions.

The story ends with J’s homecoming after one of her periodic and protracted prowls through sleazy bars and flea-bitten hotels- outings that have Aunt V distractedly combing the waterfront and B, from loneliness, indulging her gluttony. At last, B sees J in her doorway:

“Hi, kid, mom whispered as she crept into my room out of the rain which had fallen through so many nights, had perhaps started that night when she had last disappeared, or so it seems to me now. Her rain-glazed face was swimming out of the door frame, toward my bed. And there was on her breath that mysterious odor I well remember from other nights when she’d surface after her trip through oblivion: an odor no longer of gin but of something more highly distilled, rarefied, and almost otherworldly like a liquid reserved for angels. Rain dripped from her poncho onto my face, my eyes as she was standing over me, trying to smile. Hi, kid. Hi, Mom. My face was wet with rain.”

“The beauty and magic of The Talking Room,” Larry McCaffery writes in Contemporary Literature (Winter 1978), “is difficult to analyze. The key would seem to be in the book’s extraordinary prose patterns, which create in their complex, interrelated images a sustained vision of loneliness, the desire for love, and the necessity for escape, and always a haunting, dreamlike lyricism.”

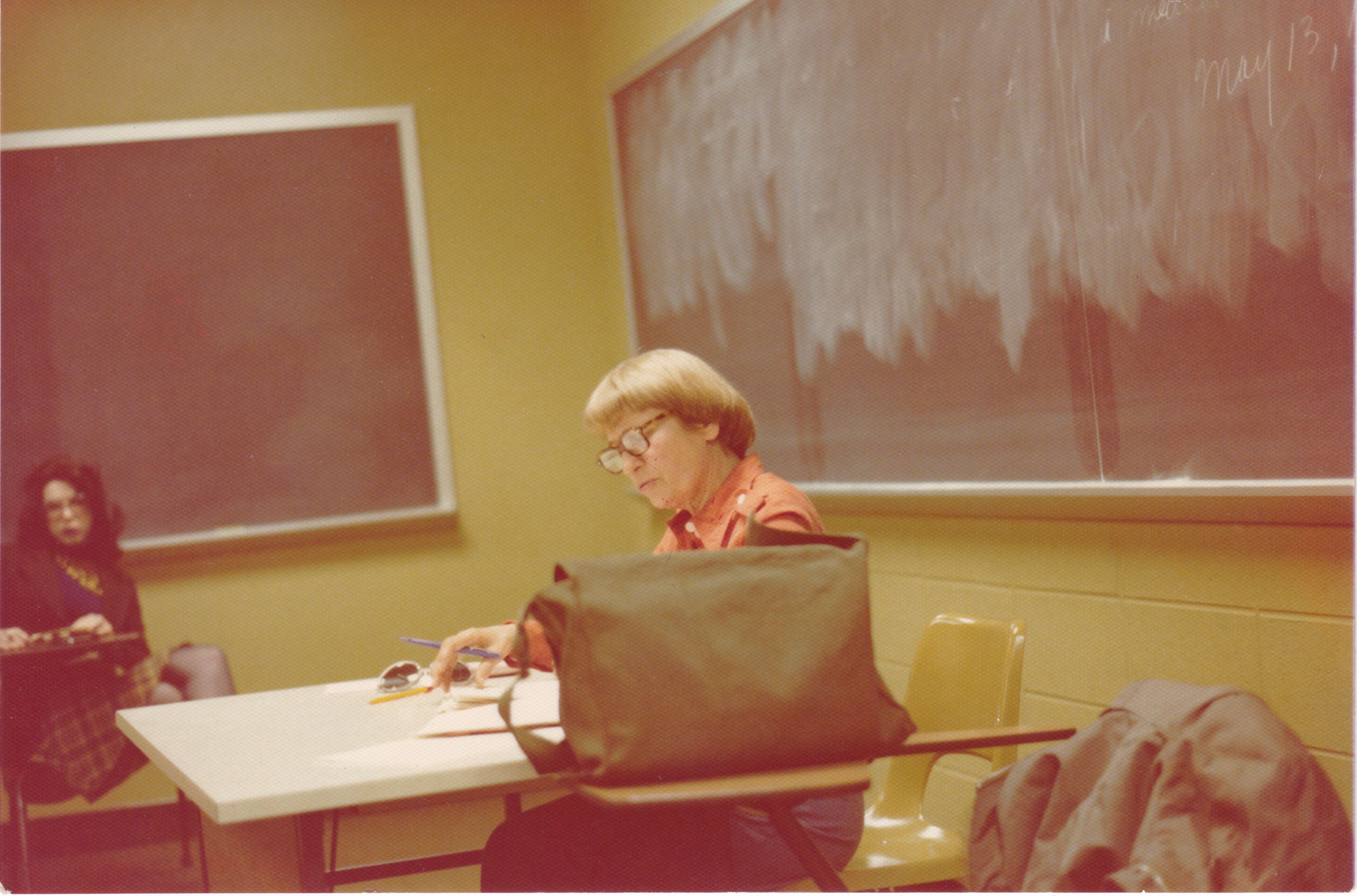

Since coming to the United States in 1937, Marianne Hauser has lived in Greenwich Village and, with her former husband, musician and com poser Frederick Kirchberger, in the South and Midwest. She has spent time in the Pacific North west and Alaska with her son, Michael, a filmmaker; has traveled from Spain to North Africa, and from Yucatan through Guatemala to Peru. In the spring of 1980 she visited Brazil. Her spontaneous travels are reflected in her books, especially her story collection, A Lesson in Music.

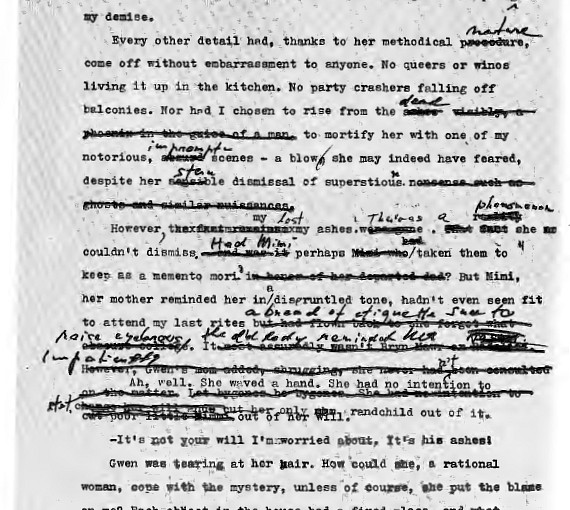

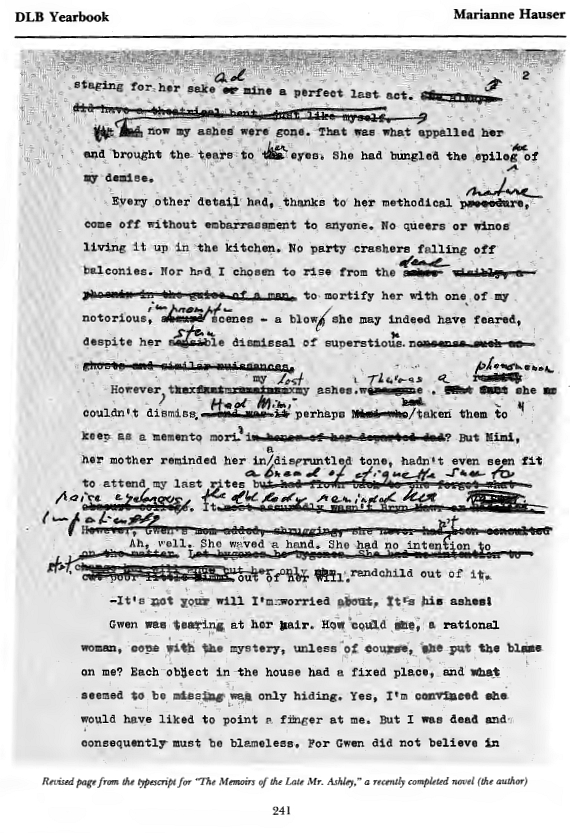

For the past fifteen years her permanent address has been Manhattan; she has taught at QueensCollege (1966-1978) and New York University ( 1979). At present she lectures, studies Tai Chi, and, under an NEA grant, is completing a new novel: “The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley.” The narrator, an actor manque, is dead and cremated, his ashes lost. But his voice- mischievous, arch, and inescapable- is fiercely alive, directing his own doom (or salvation?); his tragicomic figure emerges as the prototype of today’s antihero.

As a private individual, Marianne Hauser is by nature adventurous, intrepid, intelligent, and witty. She is adamant and active in her stand against war and discrimination. Irreverent, even mocking, to ward accepted norms, she finds pretense a subject for ridicule. The only thing she holds sacred is the human being- hapless, abused, absurd, and beautiful.

References:

“Anais Nin on Marianne Hauser,” in Rediscoveries, edited by David Madden (New York: Crown, 1971), pp. 115-120;

John Tytell, “666 Words on Marianne Hauser,” in A Critical Ninth Assembling , edited by Richard Kostelanetz (Brooklyn: Assembling Press, 1979).

Papers:

A collection of Marianne Hauser’s manuscripts is at the University of Florida Library, Special Collections.

Morris, Alice S. “Marianne Hauser.” Dictionary of Literary Biography 1983, 238-42. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1984.