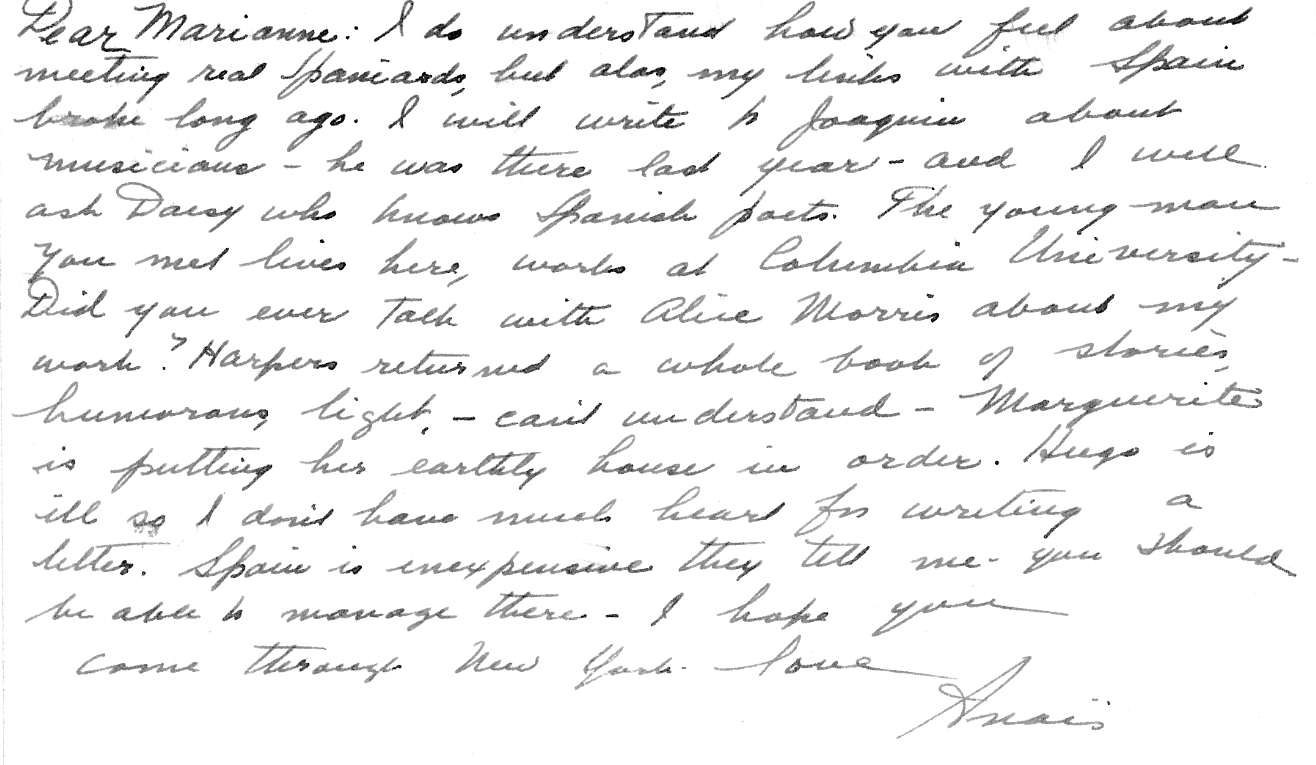

This is an evolving bibliography. It lists Marianne Hauser’s major publications. It is not complete for a number of reasons. One, I’m not a scholar. Just formatting this takes me a long time. Second, the online bibliographies are contradictory and incomplete. For instance, one lists the publisher of Heaven 2 as ‘Hallwalls‘. Hallwall’s published this story, yes. Hallwalls (click to read its history) is a non-profit arts organization in Buffalo, New York. It has galleries and performance spaces and has been a vital venue since the seventies for experimental, innovative and challenging art. Hauser read there in the 80s in a fiction series curated by Ed Cardoni, who is now Hallwall’s executive director.

I will have much to say about Hallwalls and Ed Cardoni. Cardoni edited a serial with stories and pieces featured in the series. The name of that publication is Blatant Artifice, and it is in Blatant Artifice 2 that Hauser’s strory appears, along with work by Ray Federman and Mark Leyner. I recommend it to anyone who wants to read great short fiction.

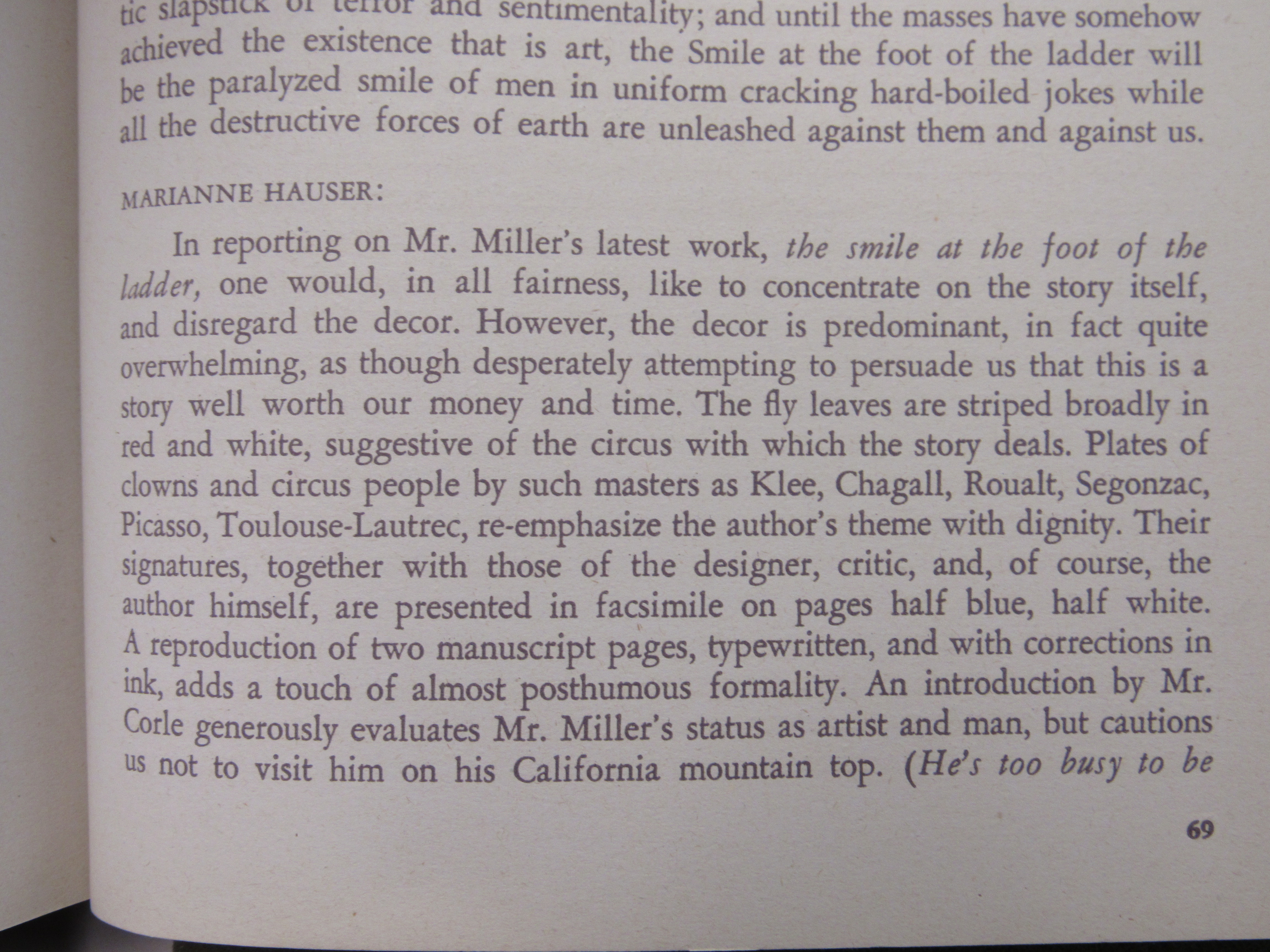

I plan on publishing bibliographies of Hauser’s reviews here as well (she wrote 80+ reviews for the NYT alone between 1940 and 1943), and will update this bibliography as I get more information. If readers see errors, or know of publications not listed, please send me an email: jon at lastbender dot com.

Marianne Hauser Evolving Bibliography

Novels and Collections

Monique. Zurich: Ringier, 1934.

Indisches Gaukelspiel (Shadow Play in India). Leipzig: Zinnen, 1937.

Dark Dominion. New York: Random House, 1947.

The Choir Invisible. New York: McDowel, Obolensky, 1958. Published in England under original title, The Living Shall Praise Thee. London: Gollancz, 1957.

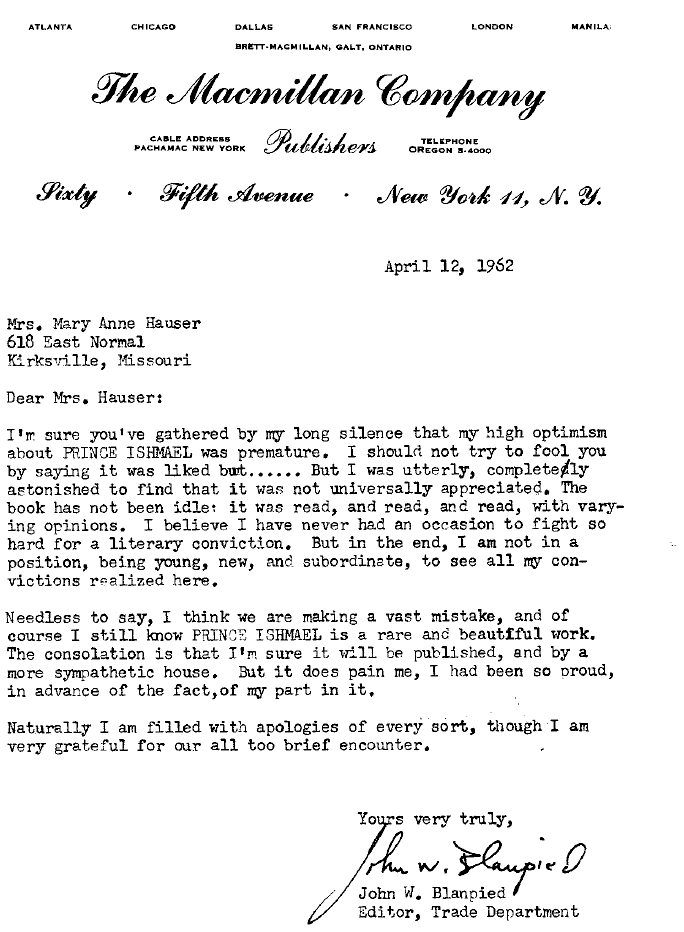

Prince Ishmael. New York: Stein and Day, 1963. Reprinted, Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Classics Series, 1991.

A Lesson in Music. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964.

The Talking Room. New York: Fiction Collective, 1976. Excerpt in: Sukenick, Ronald and White, Curtis. 1999. In the Slipstream: An FC2 Reader. Normal/Tallahassee: FC2.

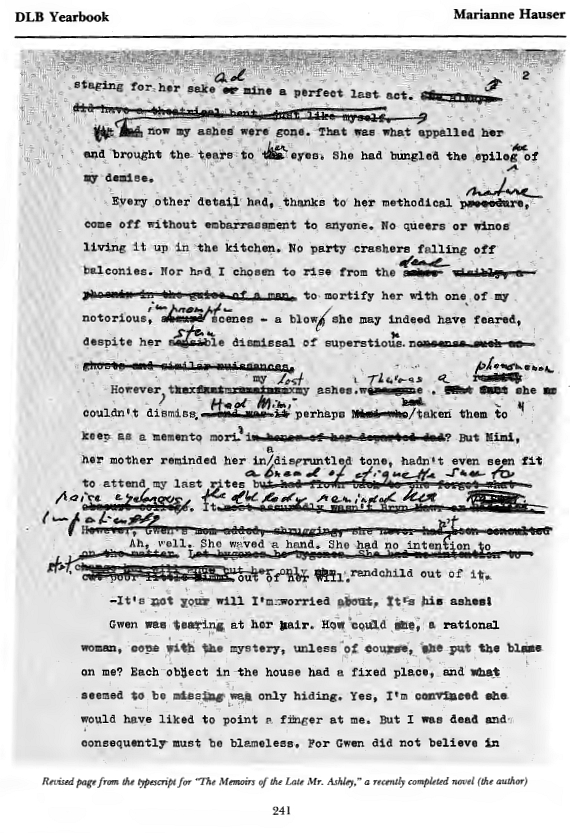

The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley: An American Comedy. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press, 1986. Trans. In German, Suhrfkamp, 1992.

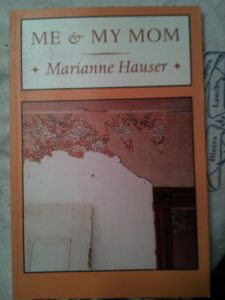

Me and My Mom. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Classics, 1993. Excerpt: Scandal at the Bide-A-Wee Nursing Home for Mature Seniors. Fiction International 22, 1992.

Shootout with Father. Normal [Ill.]: FC2, 2002.

The Collected Short Fiction of Marianne Hauser. Normal [Ill.]: FC2, 2004.

Uncollected Stories

The Colonel’s Daughter. The Tiger’s Eye 3,March 1948, 21-34.

The Rubber Doll. Mademoiselle, 1951.

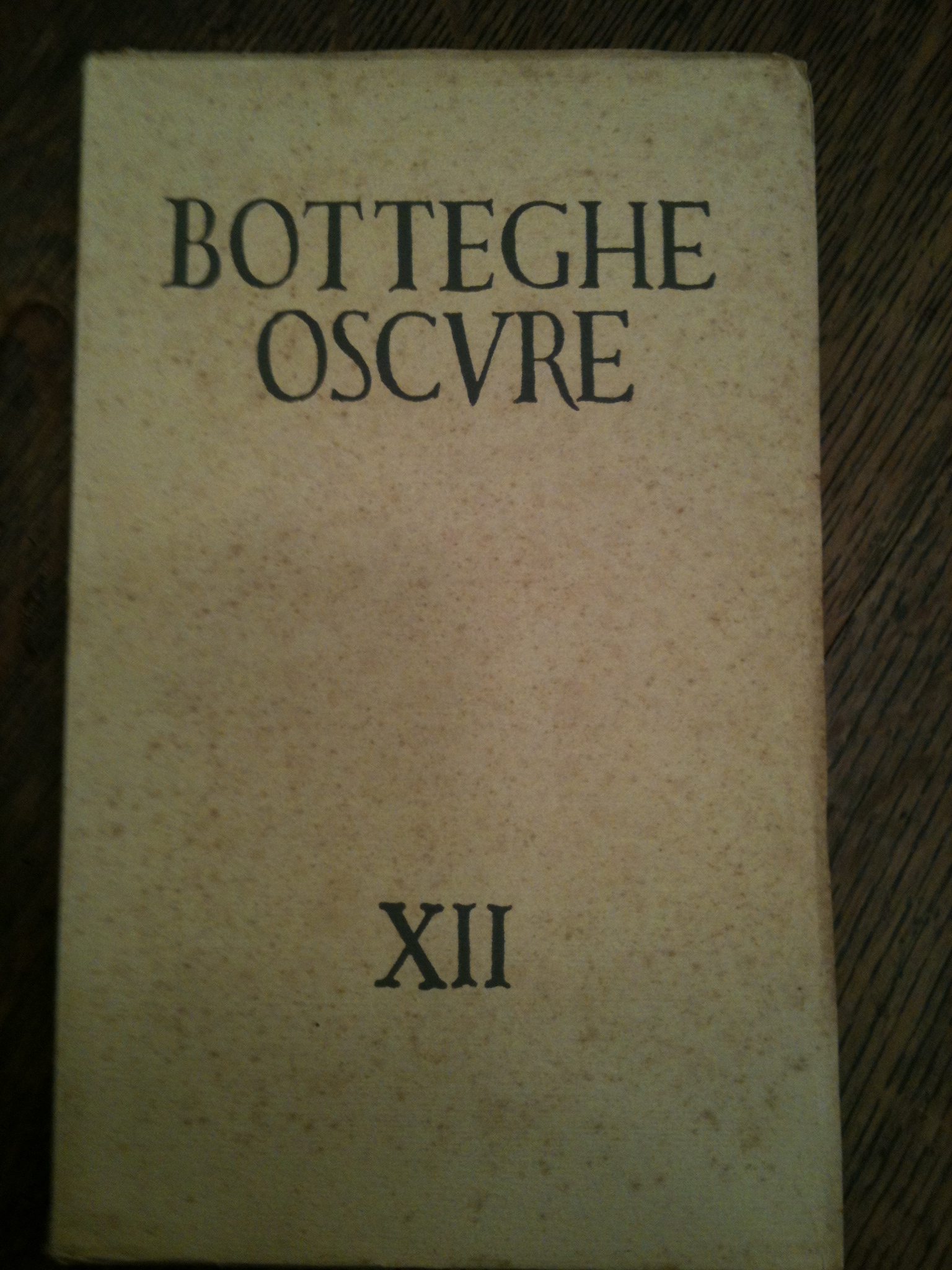

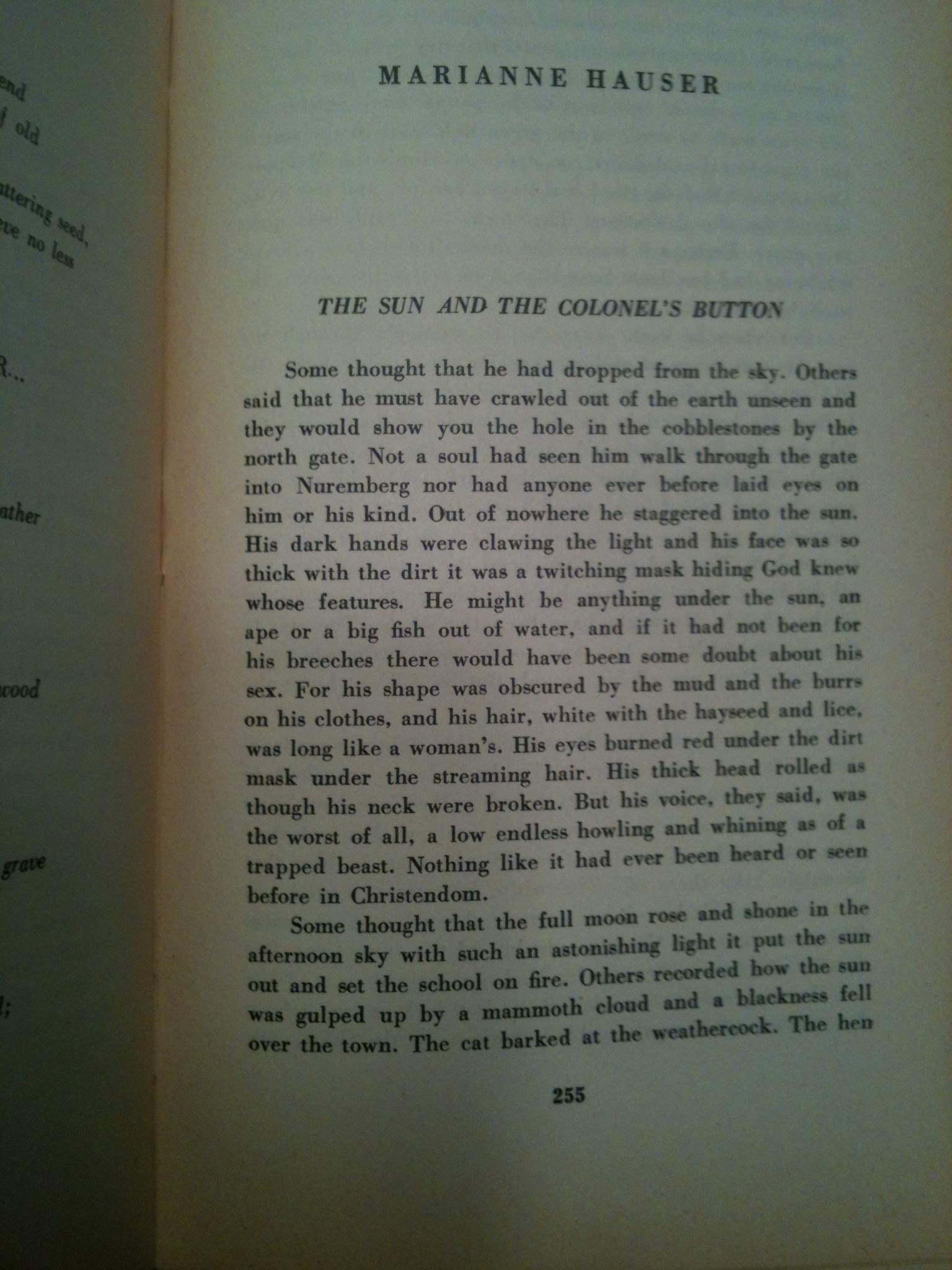

The Sun and the Colonel’s Button. Botteghe Oscure 12, Fall 1953, 255-72.

note: first chapter of Prince Ishmael written in the 3rd person.

Nonfiction, partial list of American publications

The Indomitable Spirit of Alsace. Travel 70, 1938, 28 –.

Swan Song of the Middle Ages. Travel 72, 1939.

Pantomime in Blue and Silver. Travel 72, 1938, 18 – .

Bamboo, Symbol of Old China. Travel. 73, July 1939, 30.

Successful Small Home That Suits the Environment. Arts and Decoration 49, February 1939, 18 – .

Home Industries of the Swiss Peasants. Arts and Decoration 50, April 1939, 22–40.

Marrakesh: Descent into Spring. Harper’s Bazaar, May 1966, 188-203.

Story Collections

A Lesson In Music. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964.

Contents:

Introduction

Allons Enfant. Harper’s Bazaar, August, 1962.

The Cruel Brother. Mademoiselle, October, 1945.

Peter Plazke, Poet. Perspective, 1955.

One Last Drop for Poor Abu

A Lesson in Music. Harper’s Bazaar, May, 1946.

The Mouse. The Tiger’s Eye 8, June, 1949, 88-98. Reprinted in Foley, Martha. 1950. The Best American Short Stories 1950. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin.

The Other Side of the River. Mademoiselle, (April 1948). Reprinted in Brickell, Herschel. 1948. Prize stories of 1948: the O. Henry Awards. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

The Dreaming of Poseidon. Harper’s Bazaar, September 1961.

The Island. The Texas Quarterly, Winter, 1959.

The Sheep. Harper’s Bazaar, May, 1945.

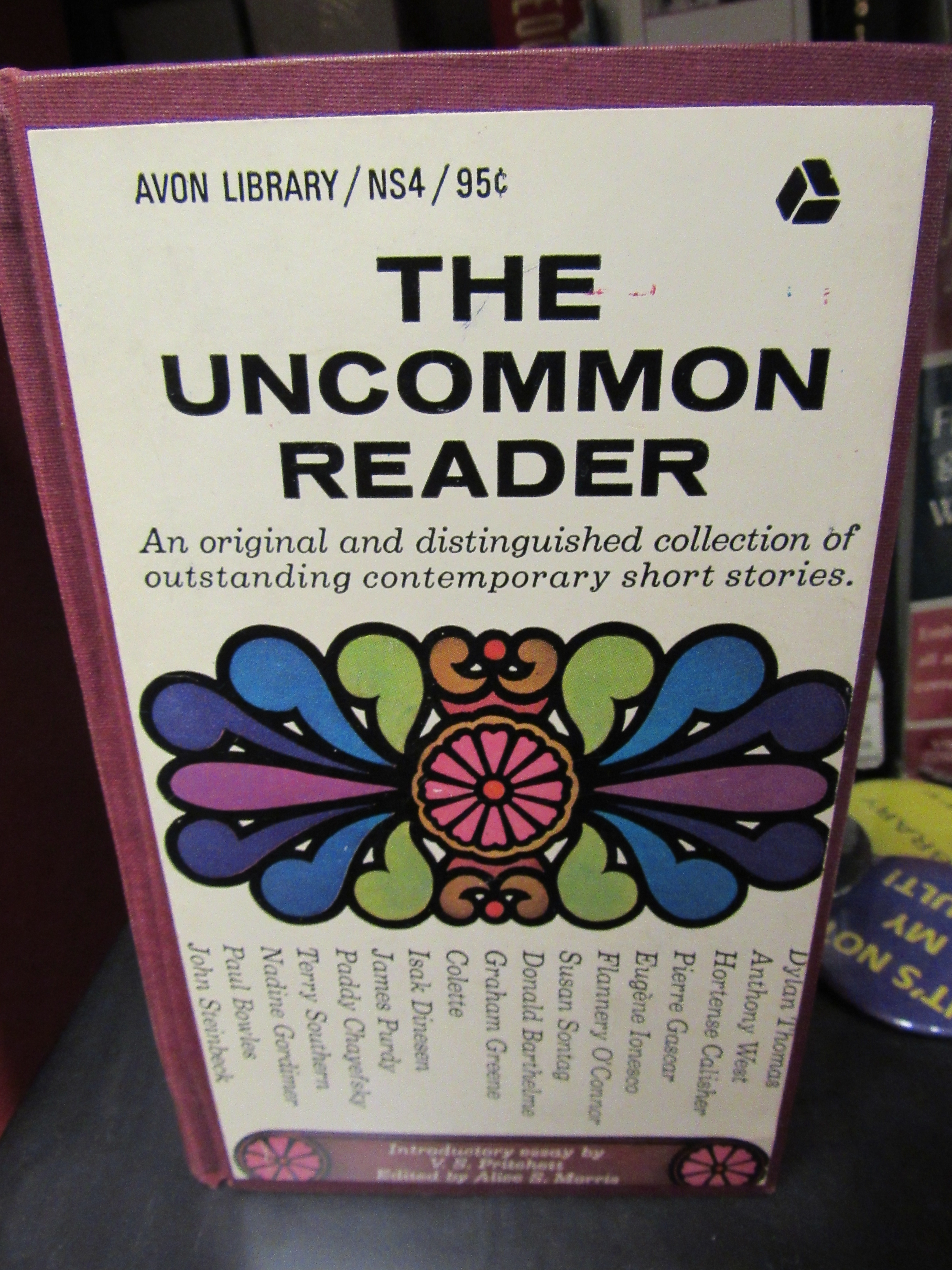

The Abduction. Harper’s Bazaar, 1964. Reprinted in: Morris, Alice S. 1965. The Uncommon Reader. New York, N. Y.: Avon Books. And Gold, Don S. 1967. Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company.

The Collected Short Fiction of Marianne Hauser. Normal [Ill.]: FC2, 2004.

Note: introduction written by Marianne Hauser

Contents

A Lesson in Music*

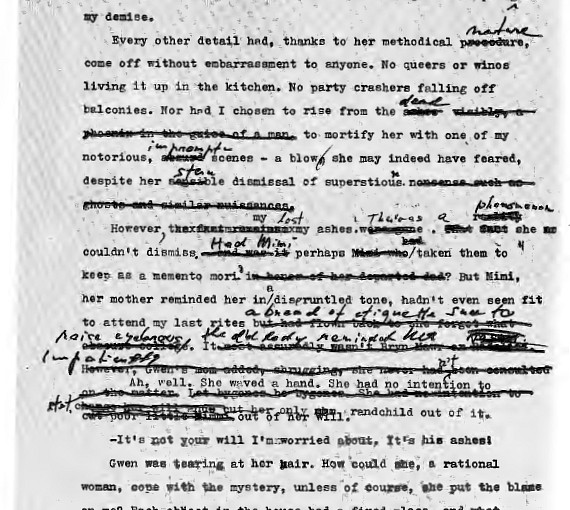

ASHES: a fragment from a novel in the making. Statements 2: NEW FICTION, edited by Jonathan Baumbach and Peter Spielberg, with an introduction by Robert Coover, Fiction Collective, New York, 1977. (Ashes is an early version of chapter one of The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley: An American Comedy).

The Other Side of the River*

Mimoun of the Mellah Harper’s Bazaar, (December 1966): 114-82.

Heartlands Beat. Fiction International 18, 1 (Spring 1988): 11-22.

Peter Plazke, Poet*

The Sheep*

The long & short: a fable

The Cruel Brother*

The Seersucker Suit. Carleton Miscellany 9 (Fall 1968): 2-14. Reprinted in American Made: New Fiction from the Fiction Collective, ed. Mark Leyner, Curtis White, and Thomas Glynn, 93-106. New York: Fiction Collective, 1986.

Weeds. Denver Quarterly

Heaven 2. Blatant Artifice, Hallwall’s Fiction Anthology. vol 2. ed. Edmund Cardoni. Buffalo: Hallwalls, 1986.

The Dreaming Poseidon*

Conflict of Legalities. High Plains Literary Review.

The Island*

No Name on the Bullet. Fiction International 19, 2.

The Missing Page. Witness 1, 2/3.

It Isn’t So Bad It Couldn’t Be Worse. City 9 International Anthology.

Allons Enfants*

My Uncle’s Magic Machine Fiction International 34, (Fall 2001).

The Abduction*

*= published in A Lesson in Music