Marianne Hauser was born in 1910. Her early life was shaped by the two world wars: her earliest memories are of Strasbourg in the teens, her sister’s death, her father’s working in a German munitions plant, marching off to the bomb shelters singing the song, Allons Enfants, smuggling eggs. In her few autobiographical writings World War 1 is both tragic and a caper, an event that divided the loyalties of her relatives. Her family was German. But they lived as Alsatians, the only identity she embraced her entire life. In the story Allons Enfants her uncle is a member of an underground organization in favor of Alsatian independence. The duality, or tripling of identity informed her work. World War 2 on the other hand, and the Nazis, has no aspect of the caper about it. Hauser loathed the Nazis and was deeply disturbed by her father’s decision to move to Germany in the twenties, and remain until his death in the forties. Her mother died in the forties too. She did not see them after the late thirties, perhaps 1937 or ’38. At some point in those years she skied with her father in Switzerland, and saw her mother in Paris. Her husband, Fred Kirchberger, escaped the Nazis and joined her in America. His brother, Hermann, had married Eva Hauser, Marianne’s younger sister. They are listed as holocaust survivors. I have been able to learn very little about them, even from Michael Kirchberger. The fact is Marianne and Fred were not interested in discussing the past. Yet in the 30’s, in New York, Hauser lectured on the threat of Nazism, addressing church and civic groups. Her beat as a reviewer was the war. The vast majority of her NYT book reviews are of books dealing with Fascist Europe. The same is true for her Saturday Review pieces. I haven’t seen the New York Herald Tribune reviews, but I suspect the same is true there. These were written in the early forties.

Her fiction is full of references to Nazis, fascism, the police state, and often, a character who meets a German and calls him a Nazi. Here is a piece Michael Kirchberger sent me. It is about a review she read in the New York times of Leni Riefenstahl’s autobiography. I don’t know if it was ever published.

Category: UNCOLLECTED/UNPUBLISHED

ALICE S. MORRIS: A FIERCE CONTEMPT FOR BIGOTRY

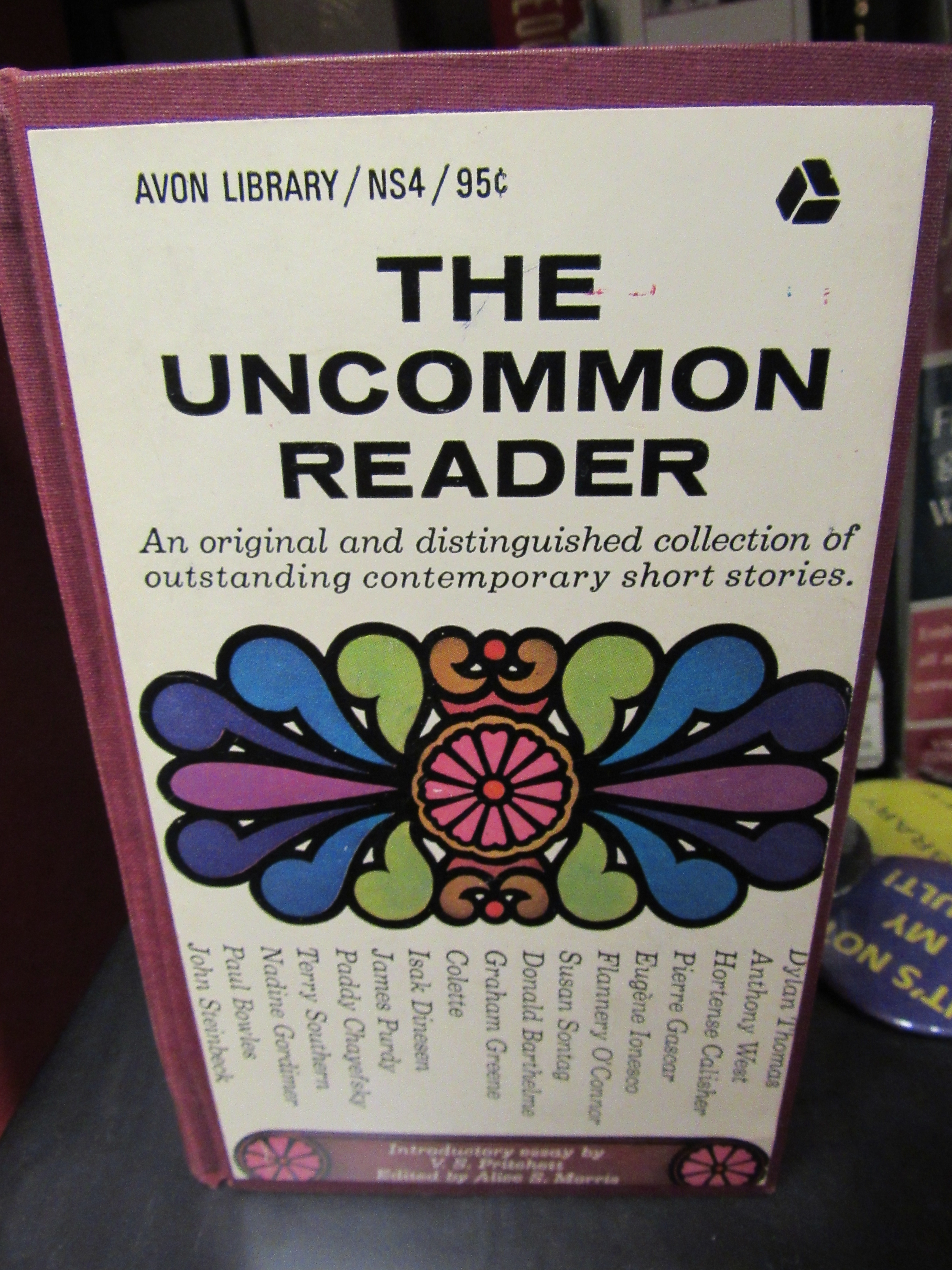

Alice S. Morris was one of Marianne Hauser’s closest personal friends, and she was also a vitally important professional friend. Morris was the literary editor at Harper’s Bazaar from 1951-1968 and she published many of Hauser’s stories, as well as excerpts from her novel Prince Ishmael. In 1965 she edited The Uncommon Reader, a collection of Harper’s Bazaar stories which includes Hauser’s The Abduction, an hallucinatory journey into exile taken by a Hungarian composer. It is based largely on the life of Erno Dohnanyi, whom she knew in the 1950’s, in Tallahassee, where he was teaching and where Fred Kirchberger got his PhD. Morris died at age 90 in 1993. Alice S. Morris was one of several adventurous mid-century editors at fashion magazines. These women’s magazines became a market for serious literary fiction. She was preceded by George Davis, who was at Harper’s Bazaar from 1936-1941, who then moved to Mademoiselle until 1949. Betsy Blackwell was the editor and chief of Mademoiselle from 1937-1971. Mademoiselle was a Conde Nast publication, which for a time was a partner of McBride’s, where Coby Gilman worked editing Travel. Carson McCullers, Truman Capote, Jean Stafford, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, James Baldwin, Jane Bowles, Paul Bowles, and Tennessee Williams are some of the many authors published by these fashion magazines early in their careers. When Hauser published Dark Dominion her friend Marguerite Young reviewed it in Vogue alongside McCullers’ A Member of the Wedding and Capote’s short stories.

Morris was married to Harvey Breit, a novelist and editor who reviewed books for the Times in the 40’s (his Times obit gives different dates than the Wikipedia article for his NYT tenure). When she died, Hauser wrote this about her old friend: