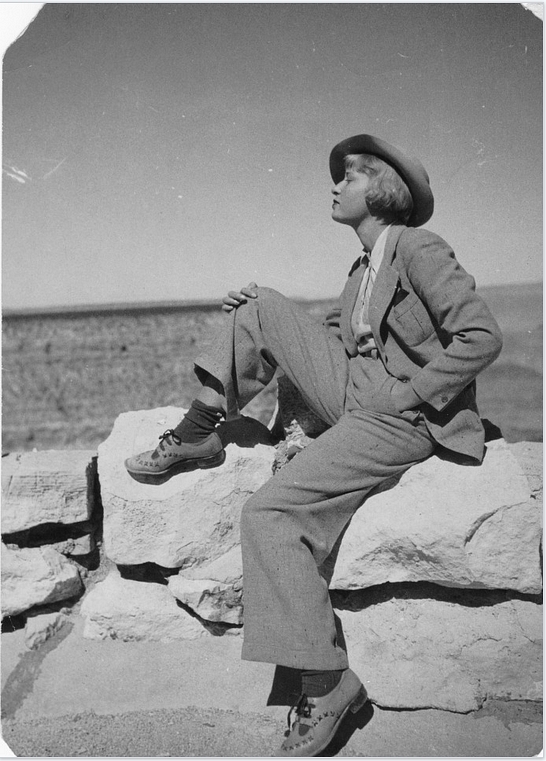

This piece, remarks delivered by Hauser at some public forum I can’t yet identify, convey (according to her son) what she was like in life, quick witted, funny, and impatient with moralizing idiots. This persona definitely comes through in her interviews but here she is engaged with an audience, and explains a fundamental part of her aesthetic: the imagination is capable of inhabiting, and expressing, the experience of others, not just the author. Fiction was her way of knowing things. Without this belief her entire body of work goes away, as she chose only twice to write novels (at least in English) from the point of view of a woman. These are The Talking Room (1976), whose narrator is a 13 year old American girl, pregnant, and being raised by lesbians, and Me and My Mom (1993), a story told by a woman in her 30s (I’m guessing, her age isn’t specified) who puts her old, and increasingly demented mother in a nursing home. Hauser dedicated the book to her old friend and mentor, Coby Gilman, who died in his seventies, alcoholic, and alone. Me and My Mom was published 26 years after his death and burial in a numbered mass grave in Potters Field. She gave this talk in 1984, and refers to the novel she was writing at the time, The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley (1986), which, like Shoot Out With Father (2002) is narrated by a gay man. She discusses both Prince Ishmael (1963) and Dark Dominion (1947) and refers to a book review she wrote for the Times in the early 40s. I am trying find which of the dozens of Times reviews she wrote she is talking about. When I do I’ll post it.

This piece, remarks delivered by Hauser at some public forum I can’t yet identify, convey (according to her son) what she was like in life, quick witted, funny, and impatient with moralizing idiots. This persona definitely comes through in her interviews but here she is engaged with an audience, and explains a fundamental part of her aesthetic: the imagination is capable of inhabiting, and expressing, the experience of others, not just the author. Fiction was her way of knowing things. Without this belief her entire body of work goes away, as she chose only twice to write novels (at least in English) from the point of view of a woman. These are The Talking Room (1976), whose narrator is a 13 year old American girl, pregnant, and being raised by lesbians, and Me and My Mom (1993), a story told by a woman in her 30s (I’m guessing, her age isn’t specified) who puts her old, and increasingly demented mother in a nursing home. Hauser dedicated the book to her old friend and mentor, Coby Gilman, who died in his seventies, alcoholic, and alone. Me and My Mom was published 26 years after his death and burial in a numbered mass grave in Potters Field. She gave this talk in 1984, and refers to the novel she was writing at the time, The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley (1986), which, like Shoot Out With Father (2002) is narrated by a gay man. She discusses both Prince Ishmael (1963) and Dark Dominion (1947) and refers to a book review she wrote for the Times in the early 40s. I am trying find which of the dozens of Times reviews she wrote she is talking about. When I do I’ll post it.

Category: Exhibitions

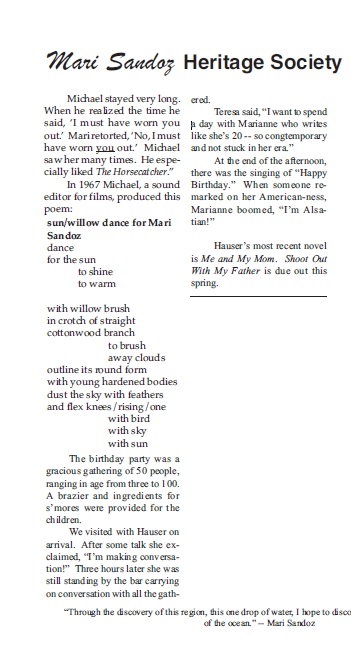

Hauser and Sandoz

This is a profile of Marianne Hauser, written for the Mari Sandoz Heritage Newsletter, Spring 2001, by Richard F. Voorhees. The occasion was her 90th birthday and the place was New York, where she lived. This profile is fascinating for the light it sheds on one of Hauser’s most important, and best, books, The Memoirs of the Late Mr. Ashley. (The Publisher’s Weekly review of the book is beyond idiotic! Read mine instead). According to Voorhees the model for Mr. Ashley was a man named Wesley Towner, one of Hauser’s close friends and drinking buddies, and the author of The Elegant Auctioneers. In the novel, Ashley is supposed to be writing a non-fiction opus about southern mansions, his lack of production notoriously disguised by the tape recording of a clacking typewriter. Towner, unlike Ashley, mostly completed his book before dying. Towner’s family owned the building Mari Sandoz lived in. In this profile Voorhees also discusses how Sandoz and Hauser became friends, and the encouragement Sandoz gave her when writing The Choir Invisible. Richard Voorhees is a fascinating man in his own right. It’s not a surprise that he and Hauser would hit it off.

Allons Enfants

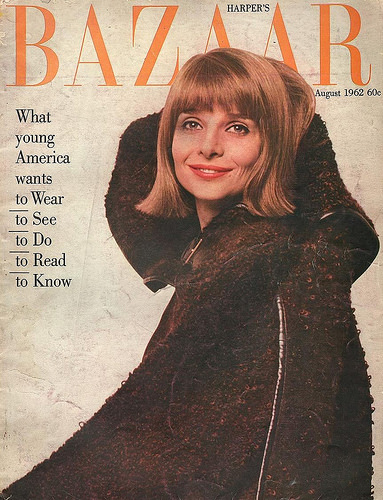

This is the cover of the August, 1962 Harper’s Bazaar where Allons Enfants first appeared. Allons Enfants is one of two autobiographical stories Hauser wrote, set in Strasbourg during World War 1. It narrates the death of her sister Dora at age 17 of meningitis and is delirious with detail of her family and the city. It also appears in her first collection of short stories, A Lesson in Music (University of Texas Press, 1964) and is currently in print: The Collected Short Fiction of Marianne Hauser (FC2, 2005). Alice S. Morris, her close friend, was the literary editor at Harper’s and was renown for the fiction she published.

Hauser on Miller

Marianne Hauser published three pieces in The Tiger’s Eye, an avant-garde arts magazine published by poet Ruth Walgreen Stephan and her husband, artist John Stephan, from 1947-1949. This is Hauser’s review of a Henry Miller book, from the October, 1938 issue, #5. It is one of 4 opinions in an article entitled To Be Or Not: 4 opinions on Henry Miller’s book The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder. Hauser was good friends with Anais Nin, who published a piece in the first issue of The Tiger’s Eye. She makes brief appearances in Nin’s diaries of the 60’s and 70’s, when they were neighbors, but Hauser refused Nin permission to publish more entries, and I wonder what’s in those unpublished diaries. Weldon Kees also appears in this article, and likes the book even less than Hauser. Given that these people were all friends, it is striking how honest she is, but then, she was like that, as her comments about her future publisher Bennett Cerf, in an review of Gertrude Stein’s Ida for the New York Times (1941) make clear.